All aboard the privatisation express

The legacy of John Major’s privatisation of British Rail is still felt by passengers today, but Labour’s refusal to support rail nationalisation may be a signalling failure.

In the early years of the Thatcher government, privatisation was a means to an end. Promised as a way to reduce public spending by selling state-run entities while improving service quality through competition, it remained subordinate to other economic priorities, including wage suppression and controlling inflation.

But the Tories soon became addicted to the market. By the time the Second Summer of Love of 1989 had birthed acid house and unlicensed raves, the Tories had given into cravings and sold off Rolls Royce, Britoil, British Gas, British Steel, and British Airways. Then came water and electricity.

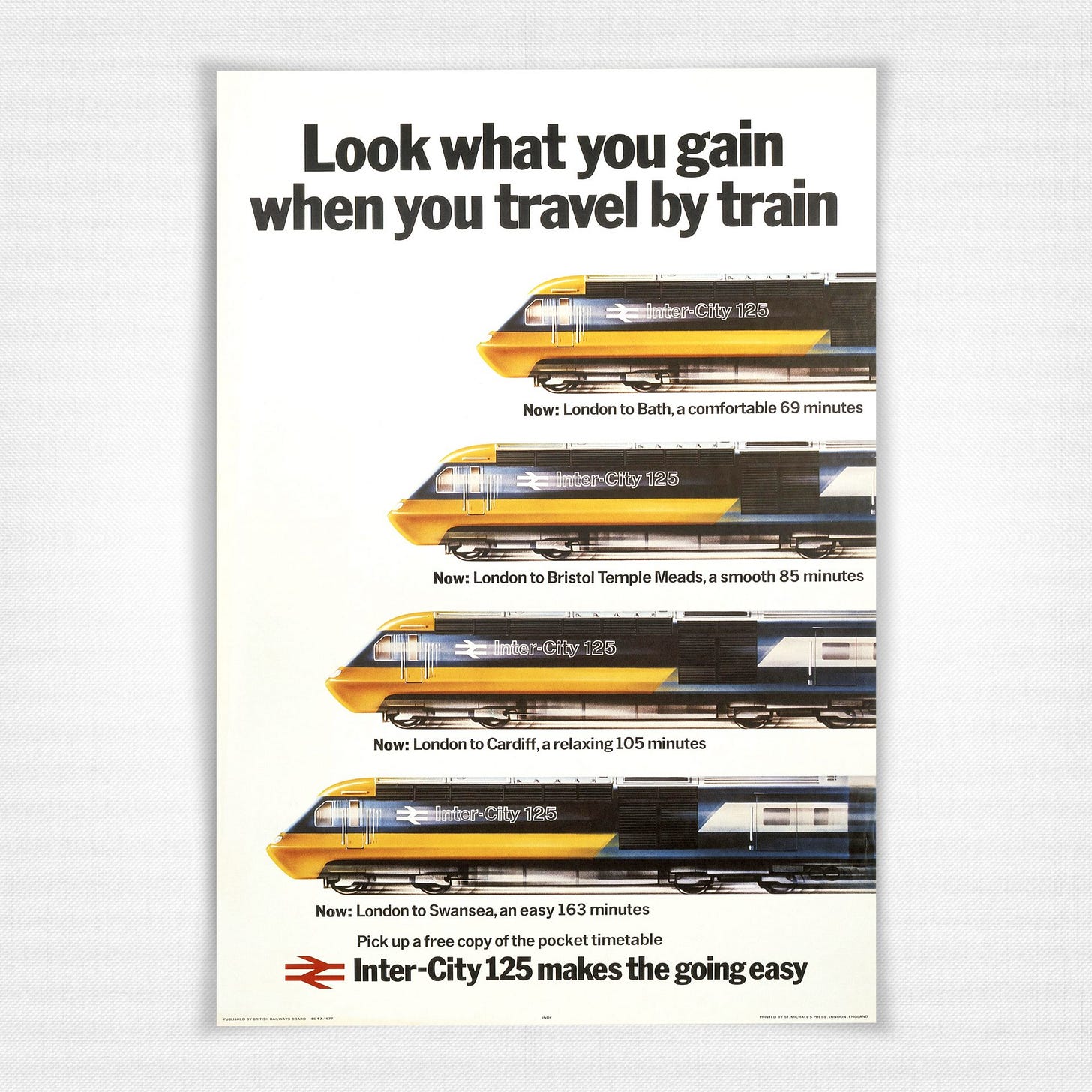

No longer a means to an end, privatisation became a panacea for British capitalism, entrusted with boosting efficiency, national competitiveness, and attracting foreign investment. The Thatcher government imposed selloffs on the public sector, often in the face of stiff opposition. But there was one state-owned firm that even Thatcher had flinched at privatising: British Rail.

John Major inherited his party’s addiction and upheld his predecessor’s pursuit of marketisation with stubborn rigidity. By 1993, the party was feening for something to sell. British Rail, with its supposedly curly sandwiches, looked tempting.

Next stop, marketisation

“There is barely a single person in this country outside Downing Street who thinks it is a good idea to privatise British Rail.”—John Smith

The problem with railway privatisation, and perhaps the reason why Thatcher was reluctant to take it on, is that fostering competition is incredibly complicated. Trains can’t overtake. Operators can’t race their competitors to stations to pick up passengers. Without competition, the promised efficiency gains would struggle to materialise.

John Major’s favoured privatisation model was to divide the rail network into geographical regions. A single firm would be responsible for the track, stations, carriages, locomotives, and passenger services in each region. There would be no competition from other firms, but the service providers would reap the benefits of any infrastructure improvements they made to enhance their services, thereby incentivizing private sector investment across the rail network.

Instead, at the behest of Chancellor Norman Lamont and his privatisation guru, Steve Robson, the government went with a proposal put forward by the Adam Smith institute. The Railways Act of 1993 broke British Rail into three components and sold them off separately.

Rail infrastructure, including tracks and signalling, went to a single private company, Railtrack. Stock, like locomotives and carriages, went to rolling stock companies. The rights to operate passenger services were then franchised out to operating companies that would lease stock and stations from rolling stock companies and pay Railtrack for access to the track infrastructure.

The assumption was that competition could be introduced at the bidding stage. Rival operating companies would fight to present a bid that would generate the highest profits with the best service.

In practice, separating rail infrastructure and stock from operations created an unwieldy morass of more than 100 companies across the rail network. A turgid web of contracts that governed inter-firm relationships provided lawyers, consultants, and accountants with plentiful hosts to bleed dry. It even went against Thatcher’s grain: managing this bureaucratic mire would require even more oversight and government regulation, not less.

Delays on platform 3

“The whole thing is falling apart before they even get started. Nine days before the supposed big launch day on April 1 for rail privatisation, Mr MacGregor (Major’s Transport Secretary) has been forced to admit his madcap scheme cannot possibly work."—Frank Dobson, Labour Transport Spokesman.

On April 1, 1994, all 23,500 miles of track and 2,500 stations would transfer from British Rail to Railtrack. The bidding process for the 25 franchises would also open. The government had set a target of awarding at least 51 percent of routes to franchises in the next two years.

A harbinger of the chaos to come, the plan almost immediately hit delays. So few private companies were interested in the initial franchises that the government was forced to hold the options open for another year until 1995.

A derailed legacy

Initially, privatisation improved services. More trains ran, passenger numbers rose, more freight moved, and punctuality and reliability improved. But there were fatal flaws in the system.

The franchise model had distorted incentives for investment in maintaining and upgrading infrastructure. Train line upgrades can take up to a decade and new carriages and locomotives take years to make. With some UK firms bidding on 7-year leases, it was not in their financial interests to invest in upgrading services.

This misalignment of incentives would have tragic repercussions. In 1996, poor wagon maintenance caused a freight train to derail into the path of an oncoming Post Office train, killing a postal worker. A faulty Automatic Warning System was partly responsible for the Southall rail crash in 1997 that killed 6, and the Hatfield Rail Crash in 2000 killed 4 people when the train derailed over a section of broken track. As a result, Railtrack went into administration in 2001 and its responsibilities were returned to the public sector under Network Rail in 2002.

Other benefits of privatisation also failed to materialise. A 2010 review of the British rail network described a system racked with inefficiency and underinvestment where profits are funnelled to foreign governments—70 percent of all rail routes are wholly or partially owned by foreign states, with state enterprises from the Netherlands, Germany, France, Italy, and Hong Kong all running franchises.

In 1989, Britain’s railways were reportedly 40 percent more efficient than comparable European railways. 20 years later, they were estimated to be between 34 and 40 percent less efficient than the top-performing European networks. Over 600 workers were employed on “delay attribution”, essentially responsible for bickering over which company is responsible for compensating passengers after delays.

Passengers were paying more for a less efficient service. Between 1994 and 2015, fares increased by almost 30 percent once adjusted for inflation.

Most franchises were awarded without competition between bidders. In instances where there was competition, bidders frequently inflated profit predictions to secure franchises, then renegotiated contacts or simply walked away from the contracts, leaving the government to step in.

The government had essentially privatised the profits, while keeping the UK taxpayer on the hook for the risks and costs.

Change the model?

Understanding its limits, the Tory government revealed it had killed off the franchise model during the pandemic. But the Williams-Schapps proposal to replace it is franchising by another name.

The new publicly-owned Great British Railways will own the tracks, set timetables, and collect fares; operating firms will be paid to provide services with some new rewards for punctuality and efficiency.

The Conservatives argue the introduction of incentives for offering a quality service will transfer some of the cost risks onto the private sector. The inescapable reality is that the state shoulders the ultimate risk: it cannot afford to let the country go without an important rail route and will always have to step in if a private firm goes under.

The end of the line

When routes have been returned to public management, they’ve been successful. In 2009 the East Coast Main line franchise connecting London, Yorkshire, the North East and Scotland—then run by National Express—failed. The government stepped in to run the route. In addition to returning £1 bn to the public coffer, punctuality and reliability on the line improved. The Conservative government privatised it again in 2015, but it failed again three years later.

The British electorate is already convinced of the benefits of rail nationalisation. Rail is consistently among the most popular industries for nationalisation, with 63 percent of Conservative voters in favour and 78 percent of Labour voters.

There is, therefore, an opportunity for Keir Starmer’s Labour Party to commit to rail nationalisation as part of a worker-centric industrial policy.

Although Starmer supported the “common ownership of rail, mail, energy, and water” in his bid for Labour leader, the Labour leadership has since been vague about its commitment to rail nationalisation.

In July, four months after Shadow Transport Secretary Louise Haigh told a train drivers’ union journal that Labour was “totally committed” to rail nationalisation, Rachel Reeves told the BBC that “spending billions of pounds on nationalising things… just doesn’t stack up against our fiscal rules”, a view later echoed by Starmer. A Labour spokesperson clarified that Labour would be “pragmatic” about rail ownership.

On a recent appearance on Jeremey Vine, Starmer squirmed under questioning about his abandoned public ownership pledges, without once mentioning the merits of bringing rail under public ownership.

If it is indeed fiscal rules Labour are worried about, nationalisation should be on the table. Recent private sector profits suggest that operating rail services is extremely profitable. Even during the pandemic, when travel was depressed, private rail companies made £500 million—enough to give every one of the striking RMT workers a pay rise of £12,500 a year with no added strain on the public purse.

The policy could begin to mend the party’s ailing relationship with industry workers. Internal debate over public support for strikes has threatened to reveal a party out of touch with workers. As figures like Mick Lynch and Eddie Dempsey land blows to the Conservative government and see their political stock rise, rehabilitating this relationship would shore up support among progressive voters.

The policy would also integrate into Starmer’s broader policy ecosystem. Having ruled out Britain rejoining the European Union’s single market, a pledge to nationalise the railway system could be marketed as “taking back control” European countries siphoning rail profits abroad.

Starmer already rejected calls for energy nationalisation. If his approach to nationalisation is, in fact, “pragmatic” rather than pretence, rail may be the most promising remaining candidate for public ownership, given the widespread acceptance on both sides of the political aisle of private rail’s failures.

It is telling that no other country has adopted Britain’s model of railway nationalisation. Major’s rail nationalisation enterprise has failed to deliver on its promises, leaving the country with an overpriced and underperforming network. As a new prime minister leans into political nostalgia, Labour would do well to illuminate the scars privatisation has left on the rail system and offer a bold alternative vision for Britain’s passengers.

Before you go…

John Curtice has a new op-ed in the i on Starmer’s polling lead over Liz Truss.

Anthony Barnett is in Byline Times discussing the end of the ‘New Elizabethan Age’ and how sovereignty and monarchy have moved apart.

Donald Macintyre compares Truss’s cabinet choices to Thatcher’s in the i.