What if John Smith had lived?

If the former Labour Leader had survived his second heart attack, what might a John Smith government have achieved? And what would it have meant for Britain today?

If Tony Blair is to be believed, and the “hand of history” is perceptible in moments of national political gravity, then in May 1994, the UK electorate could justifiably feel like history’s hand had grabbed them by the lapel, spun them round, and thrown them unflinching to the curb like an irate bouncer dispatching a teenage drunk from a nightclub queue.

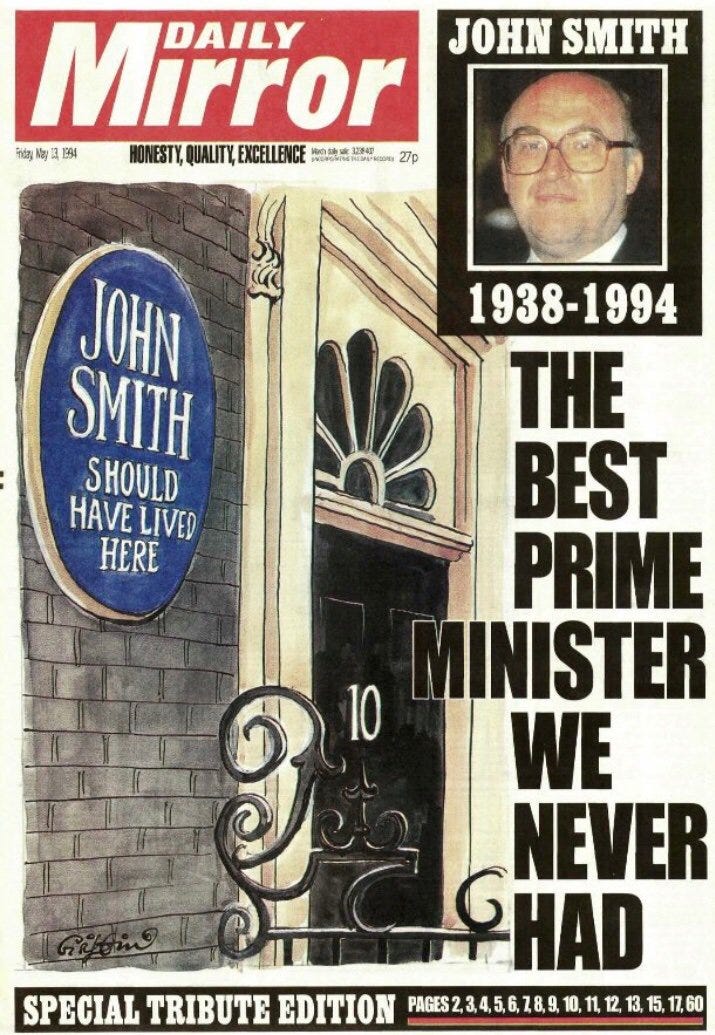

Labour Leader John Smith died suddenly of a heart attack on May 12, altering the course of British political history. Polling had Labour 20 points ahead, John Major had been exposed as an ineffective leader, his government’s reputation for economic competence was in tatters, and the Conservative Party was dogged by accusations of sleaze, making Smith the prime minister Britain never had.

It is difficult to say exactly what would have happened had Smith lived. Asking “what if” can quickly descend into conjecture. Smith was a long gamer. He was determined not to repeat Neil Kinnock’s speedy and semi-public development of policy that gave the Tories ample time to steal the policies they wanted and let the others go stale by election day. His first two years as Labour leader, therefore, offer scant details on what a hypothetical Smith government’s legislative agenda might have looked like.

Smith’s brand of politics wasn’t capricious, however. It was built on a bedrock of principles, cemented by 24 years as a parliamentarian and 15 years in the shadow cabinet. Taken together, these principles, the relationships he fostered, and his parliamentary and shadow cabinet legacy provide some insight into what a Smith administration might have looked like, and offer a glimpse of an alternative political path tragically denied to the British electorate.

Would Smith have won in 1997?

“There is a small group of rather despicable little creatures who hang around Millbank Tower, who in private will say to you, ‘we could never have won with John Smith’ and they’re very disparaging about him. None of them ever dare to say it in public.”—Ken Livingstone, 1999.

Smith would have certainly won in 1997. Conservative infighting over Europe and the calamity of Black Wednesday shattered public trust in government competence and its ability to govern. But it is unlikely that Smith would have matched Blair’s tally of 418 Labour seats.

As Labour spokesman for trade, prices, and consumer protection in 1981, Smith had forced an emergency parliamentary debate over Murdoch’s merger of the Sunday Times and the Times. Given the history, the full-throated endorsement Blair received from newspapers like the Sun may not have been forthcoming—although lukewarm support would likely have materialised once it was clear Smith was going to win.

Smithonomics

A Smith economy would likely have been more redistributive. For Smith, taxation was an instrument of social justice, not just a revenue stream. Before the 1992 election, as shadow chancellor, he had proposed increasing the top rate of income tax to 50 percent, however, he had been stunned by the public backlash, prompting Andrew Marr to speculate that he “wouldn’t have made the same mistake twice.” There are two factors that challenge this view.

Firstly, it’s not totally clear that a higher top marginal rate of income tax was the electoral “mistake” that Marr indicates. Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats endorsed a higher marginal tax rate before the 1992 election, picking up a combined vote share of around 52 percent. A majority of the UK electorate, therefore, backed parties in favour of higher taxes on those that could most afford it.

Also, it is highly likely that Gordon Brown would have been chancellor in a Smith government. As shadow chancellor under Blair, Brown considered introducing a 50 percent top tax rate but was overruled by the Labour leader. Smith would have been far more likely to agree had Brown put the same proposal to him.

Smith also supported signing on to the Maastricht Treaty’s social chapter, which promised to strengthen worker rights, and the introduction of a national minimum wage. However, it is unlikely Smith would have devolved responsibility for setting the minimum wage to a quango, and would have consequently left his government vulnerable to attack whenever a firm closed or jobs were lost as a result of the higher rate.

An independent central bank?

David Ward, Smith’s head of policy, recalls Smith’s interest in greater transparency in policymaking. That instinct, Ward told IFCTC, would have pushed him to make the Bank of England’s decision-making process more open and accessible after Black Wednesday.

Smith wouldn’t have proposed full central bank independence, preferring to create a monetary policy committee with publicly published minutes to allow for full transparency in decision-making, but leaving the chancellor ultimately responsible for setting interest rates.

But if Smith was prime minister and Gordon Brown suggested full central bank independence as chancellor, David Ward thinks he would have successfully “persuaded Smith it was the move to make.”

A more holistic approach to constitutional reform

Unlike his successor, Smith recognized the importance of connecting the separate strands of constitutional reform and identified its wide voter appeal. While Blair went on to adopt a piecemeal approach to constitutional reform, ruling out a large reform bill and going to great lengths to avoid any mention of a new overall constitutional settlement, Smith’s speech at Charter 88 in early 1993 engaged with the issue in a more holistic way and articulated the need for a new framework of government.

Anthony Barnett, the first director of Charter 88, argued in openDemocracy that had Smith lived, Britain “in all likelihood would now have a written constitution, thanks to the democratic reform process Smith had kick-started.”

Having been responsible for steering the Scotland and Wales devolution bills through the commons in the 1970s before they were stifled by the referendums that followed, Smith considered the devolution of power “unfinished business” and the creation of devolved institutions in Scotland and Wales would have been a priority of his administration.

John McTernan, director of political operations for Tony Blair, argued that Smith might also have been better able to contain Scottish nationalism than Blair. As a Scot, he would have likely ensured that the vacuum of power left after Scottish First Minister Donald Dewar’s death in 2000 was filled by another senior Labour hand from Scotland (or with deep Scottish ties) like Robin Cook, George Robertson, or Alistair Darling, perhaps preventing Alex Salmond from seizing the narrative and rallying support for independence.

Would Britain have stayed out of war in Iraq?

How would Smith have handled the biggest foreign policy decision of the 2000s? Smith was leerier of American-led globalisation than Blair. This scepticism and Smith’s closer political alignment with Europe would have undoubtedly made him more hesitant about participating in the US invasion of Iraq.

“He was far more willing to listen to civil service advice, and wouldn't have dismissed the Foreign Office in the way that Blair apparently did,” said David Ward. “Nor would he have ignored the concerns of key European partners, especially the French who like the UK had a deep historical knowledge of the Middle East,” he added.

A different relationship with Europe?

The UK’s alignment with European rather than US leadership over Iraq could have fostered a very different UK-EU relationship. Siding with the Americans “damaged our European engagement,” said David Ward. Keeping out of Iraq could have strengthened the UK’s political ties with European leaders, particularly once the lies over Iraq’s nuclear capabilities were exposed.

The transactional approach to Europe that emerged under Blair and continued under Cameron might have been averted, and a deeper appreciation for the cultural and democratic aspects of EU membership might have survived.

Anthony Barnett argues that an approach that recognised the “democratic case for participation in the European Union” would have put the Remain campaign on more solid footing, which, after two decades of pursuing a transactional approach with the European Union, was limited to making economic arguments for membership.

That is not to say that Smith would have taken the UK into the single currency. On this, his thinking was closer to Brown’s than Blair’s. David Ward told IFTC that Smith wasn’t against the single currency in principle, but critical differences between the UK and other European economies made him wary of adopting the euro.

“If you compare, for instance, the UK with Germany. Germany has a higher proportion of people renting. For some people, it is a lifetime choice. Whereas home ownership here is far more common. That means that the UK economy is quite heavily geared to borrowing for mortgages, which makes us far more sensitive to interest rate changes than the German economy,” he said.

Could Smith have averted the worst consequences of the 2008 financial crisis?

The New Democrat and New Labour light touch approach to financial regulation left the banking sectors on both sides of the Atlantic vulnerable to the 2008 global financial crisis. Before he died, Smith had put Labour on a path to supporting more rigorous oversight of UK and global financial institutions.

David Ward explained in a paper for the Mile End Institute this summer how, as chair of the Economic Committee of the Socialist International (SI), Smith was leading a project to produce a successor to the 1980 Brandt Commission report—which had called for action to promote global economic and social development.

Due in 1995, Smith’s new report would have proposed reforms to global economic governance and warned about the risks of financial deregulation and the growth of derivatives trading.

“I like to think that Smith, had he lived, might have been able to persuade the US and others to be tougher on financial regulatory systems so that the global financial crisis could have been avoided,” Ward said. “Just as Gordon Brown played a leadership role in the G20 response to the crisis after 2008, perhaps Smith in the late ’90s could have helped to prevent it from happening in the first place”.

“Less so today, but back then [the UK] was always quite an important voice in these arenas,” he added.

Politics as a trend

Beyond any individual policy, Smith’s death helped establish a new mould for opposition leaders.

Tony Blair, a slick, young political upstart was the one to unseat the Conservative government in 1997. Had a veteran Scottish politician, with a dry wit and an appreciation for substance over image, brought Labour in from the cold, the Conservatives may not have selected David Cameron as their own champion in opposition—a politician clearly cut from the Blair cloth.

Blair would no doubt have still been in the upper echelons of the Labour government, but with Smith and Brown as the faces of the party, a different Westminster standard could have emerged.

Before you go…

David Ward marked the launch of the John Smith Centre’s new research blog with a tribute to the former Labour leader.

Sir John Curtice asked whether Labour can challenge the SNP’s dominance in Scotland in a piece for the New Statesman.

Anthony Barnett responded to a petition signed by leading figures on the Left that demands a post-war Ukraine become “neutral”, arguing any request for neutrality must not impinge on the country’s democratic right to decide its own economic and social trajectory.