The unnatural heir

Gordon Brown weighs up a leadership run but quickly finds he is no longer the assumed heir.

John Smith had grown into a quick and dangerous opponent for the prime minister at the dispatch box, and Labour was consistently scoring over 45 percent in polls when he died unexpectedly on May 12, 1994. A moratorium prevented any campaigning among his prospective successors until after the funeral, eight days later, but Labour’s polling lead meant the eyes of the media immediately turned to one of the most formidable duopolies in British politics.

In 1983, newly elected Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were assigned a shared office. Blair had relocated from the space he shared with Trotskyist Dave Nellist after the pair hadn’t been getting along on (although Nellist claims in the three weeks they shared an office the two had never actually sat and talked). Over the 1980s, from their close working quarters, Blair and Brown developed “one of the closest male partnerships I’ve ever seen,” according to Blair’s future sectary Anji Hunter.

The pair had complementary strengths: Brown, with deep roots in Scottish Labour, a meticulous understanding of economics, and a sharp policy mind, was the intellectual driving force of the partnership. He knew his way around the party and was a masterful debater. Blair, on the other hand, had broader interests and his charismatic communication style allowed him to connect with middle-class voters in the South and Midlands who were not traditional Labour supporters.

Both men harboured leadership ambitions. But as political allies with very similar policy priorities, if they both ran to succeed John Smith in 1994, they risked dividing their support and weakening their political cause. Smith’s death, therefore, threw up a rare moment in politics where both had to choose whether to prioritise career or political objectives.

It’s gonna be me

Peter Mandelson met Gordon Brown at his Church Street flat in Westminster shortly after 11am on the morning of Smith’s death and the two discussed the leadership question. While neither explicitly stated that Gordon would be the natural heir to Smith, it was clear to Mandelson that Brown thought he would become the sole modernising candidate and he expected Blair to support his leadership bid.

Blair had implored Brown to run for leader in 1992 and “more than once, he said I was the senior partner in our relationship,” Brown recalled in his memoir. But there were already rumblings that Blair would mount a leadership bid of his own.

On the afternoon of Smith’s death, the Evening Standard ran a piece by Sarah Baxter entitled ‘Why I say Tony Blair should be the next Labour leader’, and that evening, Alastair Campbell, then assistant editor at Today, appeared on Newsnight and predicted Blair would be the next Labour leader. That evening, Blair called Brown and made clear he would stand

A lot had changed in two years since Blair had urged Brown to stand for leader and pledged his support. His political star had been ascending, while Brown’s had dimmed slightly.

Brown had suffered political damage from Black Wednesday. As the then Shadow Chancellor, Brown had been an ardent supporter of British membership in the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), despite concerns from other Labour MPs and a certain 23-year-old Financial Times leader writer named Ed Balls. Black Wednesday and Britain’s embarrassing exit from the ERM, therefore, dented his credibility and was still fresh in the minds of MPs in 1994.

Brown’s attempts to move the party away from a tax and spend agenda and control spending commitments had also made him enemies on the Labour benches.

Meanwhile, Blair had bolstered his own standing during his time as Shadow Home Secretary, partly through his posturing in the wake of James Bulger’s murder and his use of the dead toddler as a stand-in for Britain under the Conservatives (the murder was “a hammer-blow against the sleeping conscience of the country”). His deployment of the slogan ‘tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’—coined by Gordon Brown—had proven an effective political message.

Blair had been mulling the leadership succession over for some time. In a conversation with Mandelson a few months earlier, he had speculated that Brown’s all-consuming interest in politics might be rebarbative to voters.

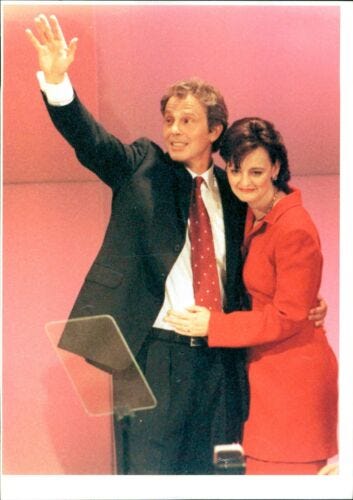

Blair thought Brown had missed his window of opportunity in 1992 when he stepped aside for Smith. In his memoir, Blair claims he told his wife, Cherie, a month before Smith died that in the event of Smith’s death, he would be leader, not Gordon.

The kingmakers assemble

Blair was in Aberdeen on the morning on May 12, where he was due to campaign for the upcoming European elections. He flew back to London at the earliest opportunity and by 6pm, he had received the backing of several prominent MPs—Jack Straw, Mo Mowlam, Adam Ingram, and Peter Kilfoyle.

Over the weekend, the Sunday papers provided an indication of his support among the wider public, putting him well ahead of other potential candidates—the Sunday Express even had him ahead among Labour-supporting trade unions, with John Prescott in second place.

Labour strategist Philip Gould phoned Brown on Sunday, May 15. Gordon asked him who it was to be. “Tony,” Gould replied.

“Tony not only met the mood of the nation, he exemplified it. He would create for Labour and for Britain a sense of change, of a new beginning, which Gordon could not do.”—Philip Gould, 1998.

Pull the daggers out or step aside

With the press becoming even more unfavourable to Gordon Brown—despite Peter Mandelson’s relentless briefings—Mandelson wrote a letter to Brown explaining the precariousness of his position and delivering an ultimatum.

He started out by praising Brown’s abilities.

“You are seen as the biggest intellectual force and strategic thinker the party has. Most people say there is no-one to rival your political ‘capacity’.”

Mandelson went on to explain that Brown’s bid was hurting from public perception that he was not the immediate front runner. Mandelson warned that Brown would either need to devise an exit strategy with “enhanced position, strength, and respect,” or go on the attack and ramp up briefings “by explicitly weakening Tony’s position.”

Brown either needed to back out or get the daggers out and publicly split with Blair, accepting the inherent risk to the moderniser cause.

Was there a path to a Brown victory?

Brown was trailing, but he had support in Scotland and believed there was a narrow path to victory by drumming up support among the left of the Parliamentary Labour Party and the unions.

The thinking went that if Brown launched a scathing campaign attacking Blair from the left—amplifying Blair’s refusal to commit to repealing new employment laws denying workers’ rights in their first two years of work—and reminded the unions of John Prescott’s decisive role in securing One Member One Vote, while his supporters embarked on a serious charm offensive, Brown might secure backing from the Transport and General Worker’s Union (TGWU). With GMB in merger talks with the TGWU, it might also follow. Support from two of the largest unions in the country might provide the momentum needed to begin to turn the tide.

However, this would have been a monumental task. Accusations of a stitch-up in 1992 had left union executives wary of making any recommendations to their members on which way to vote lest they ignite fresh accusations of another stitch-up.

Behind the scenes, union leaders said they were more interested in seeing a Labour leader elected without a contest than in fighting for any particular candidate. They were much more inclined to go with the path of least resistance, which increasingly looked like Tony Blair.

There was also no guarantee that Brown would reap the political spoils of attacking Blair from the left. It could have rallied support for a candidate to the left of Brown, like John Prescott or Robin Cook, rather than simply moved support from the Blair to the Brown camp.

Alternatively, Blair could have responded by bringing Prescott or Cook onto his ticket as deputy leader, in which case Brown would have burnt bridges with his long-time ally with nothing to show for it.

Brown, however, was not quite ready to set aside his leadership ambitions. He responded to Mandelson’s letter with instructions to continue briefing journalists on his leadership bid, but without attacking Blair. His mind, it seemed, was still not made up.

Before you go…

David Ward will be discussing what Black Wednesday and the Maastricht Treaty can teach us about Labour’s strategies in opposition today in a webinar hosted by the Mile End Institute on Wednesday, November 16, at 6:30pm.

For those following the Anthony Barnett-Yanis Varoufakis back and forth over Ukraine, Barnett delivered the next installment on openDemocracy.

Sir John Curtice examines the latest Brexit polling for UK in a Changing Europe.

Donald Macintyre remembers Guardian columnist Ian Jack.