The Edinburgh pact

Granita holds a fabled status in Labour Party lore. But the pact was hashed out over multiple meetings, most of them 400 miles away from the trendy Islington eatery.

David and Samantha Cameron reportedly stole evenings away from Downing Street at Olivocarne, a Sardinian restaurant in Belgravia nestled between a jewellers and a cigar shop, savouring choice delicacies from a menu that carries roast marrowbone, gnocchi with black truffles, and steak tartare with chopped bottarga.

Jeremey Corbyn’s preferred haunt, before it went out of business in 2018, was Gaby’s Deli on Charing Cross road—a Middle Eastern Institution known for its kebabs, falafel, and chopped liver all doled out from behind a glass counter. Tony Benn reportedly enjoyed two supermarket triple-cheese pizzas a day for years.

In the political “tag-yourself” of the London food scene, New Labour would be Granita. According to Wikipedia, the now-shuttered Islington eatery offered punters upscale modern British cuisine, “classic dishes such as mussels with exotic ingredients such as lemongrass,” complete with fizz on arrival. A spread worthy of the party of charcuterie boards and baby new potatoes.

It is perhaps the visceral allegory that helped elevate the Granita pact in the British political consciousness. In the traditional telling, Blair and Brown met at the restaurant on the evening of May 31, 1994 as competing leadership rivals and emerged of a single mind after Blair promised Brown autonomy over economic and social policy in exchange for not putting himself forward for the Labour leadership.

The moment has taken on almost mythical importance; details like Gordon Brown’s decision not to eat and who was in the restaurant at the time (EastEnders’ Susan Tully) have been dined out on. A stirring Channel 4 drama centred on the encounter immortalised the political rendezvous on the small screen. The only issue is that we now know Granita wasn’t where the deal was made.

“Tony. It’s Gordon. I’m locked in the toilet”

The deal between the two men, it was later revealed, was hashed out in a series of meetings held predominantly in Edinburgh around John Smith’s funeral. The Granita meeting, while a riveting origin story for the Blair candidacy, only served to confirm what had previously been agreed.

On Monday, May 16, The day Peter Mandelson faxed his note to Brown advising him to “escalate rapidly” or “implement a strategy to exit” the leadership contest, Blair and Brown met at the Edinburgh home of Nick Ryden, a property developer and friend of Blair.

At this meeting, Tony reportedly assured Brown that if he stood aside and didn’t fight Blair for the Labour leadership, Brown would stay on as shadow chancellor and could have autonomy over economic and social policy.

“This had some appeal,” Brown said in his memoirs, “as I would have overall control in a way I had not had under John [Smith], of what I was to call the ‘fairness agenda.’”

Shortly after Blair made the offer, Brown went to the toilet, leaving Blair twiddling his thumbs. The minutes dragged on, until Blair thought Brown might have slunk out, when Ryden’s phone finally rang. Being a guest alone in a friend’s home, Blair let it go to voicemail. According to Alastair Campbell’s diary, “GB’s disembodied voice came on: ‘Tony. It’s Gordon. I’m locked in the toilet.’”

Blair went to release him from his prison, but not before joking: “You’re staying in there until you agree.”

A murky chaser

Tony was eager for a decision, and insisted the pair meet again the next morning. At this meeting, Blair allegedly added a sweetener to his package: that if elected prime minister, he would stand down in his second term and Gordon could take over.

Brown recalls Blair framing the decision as being best for his family. By that point, Blair’s children would be in their teens and need more from him. Blair, however, contests this detail and later wrote in his memoir that he had always intended to “do two terms and then hand over.”

We may never know whether Blair in fact promised to step aside during his second term as Brown claims. However, he certainly didn’t need to. Blair was approaching the negotiations from a position of strength. It was clear that he had the support of the party, and the trade unions, and Brown would have likely stepped aside anyway to avoid dividing support for his and Blair’s brand of politics, obviating the need for further promises.

Also, the events of the Hawke-Keating government in Australia should have been fresh in Blair’s mind. Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke went back on his own succession plan in 1991, just three years earlier, dividing the party and ultimately leading to his ousting. The episode might have served as a cautionary tale for Blair and illuminated the dangers of committing to a succession plan too soon.

The pair met in Nick Ryden’s home again on Friday, May 20—the day of John Smith’s funeral. But the encounter was brief and neither provided an account of the specifics. According to Blair, the conversations with Brown “were not hostile, bitter or even unfriendly. We were like a couple who loved each other, arguing whose career should come first.”

The ambitious couple

Hard questions about the Blair-Brown marriage were taking place behind (and across) closed (toilet) doors, but the Welsh Labour Party conference that weekend threatened to drag the covert leadership contest out into the open.

Blair had declined to speak, ostensibly because of other engagements, but more likely to avoid turning the event into a media circus and drawing attention to the pair’s rival leadership claims. Brown spoke on Sunday, May 22, where he emphasised the need for unity and hinted at higher public spending.

The speech reportedly irritated Blair, who interpreted it as an appeal to the old Labour guard and the left of the party. A briefing went out to the UK media accusing Brown of appealing to “forces of darkness” in the party. Brown saw the attacks as an exercise to paint him as anti-reform and undermine his moderniser credentials. “The briefing had it’s desired effect,” he later wrote.

By the end of the week, an IPSOS/MORI poll showed that Blair was also ahead in the Midlands and the North, dampening any notion that his support was limited to London and the South.

“For much of his life, he has been tipped as a future prime minister. And now? Suddenly, he is being asked to throw away the ultimate prize, to make a brutal judgement about his capacity to reach middle Britain.”— Andrew Marr, the Independent, May 17, 1994

Blair sets out his stall

Blair had an opportunity to set out his stall for the leadership campaign two days after Brown’s Welsh Labour speech. He delivered impassioned remarks at an event on crime and family hosted by the Institute of Economic affairs.

He called for the rebuilding of the “social fabric of society” and claimed social division, inequality, and disintegration of the family and community was tearing the country apart. It was more philosophical than previous speeches and used Thatcherism as a launchpad for a scathing indictment of Tory individualism.

“There has been a recognition that unfettered liberalism will produce an atomised, uncaring, rootless society.”

But he warned against the reflex of the left to “replace this crude individualism with old notions of an overbearing, paternalistic state.”

“The task is rather one of national renewal to rebuild a strong civic society and base it on a modern notion of citizenship, where rights and duties go hand in hand. To put hope and opportunity in place of fear and decline and to match the talents of our people by the ambition of our Government.”

Three dinners and a leadership funeral

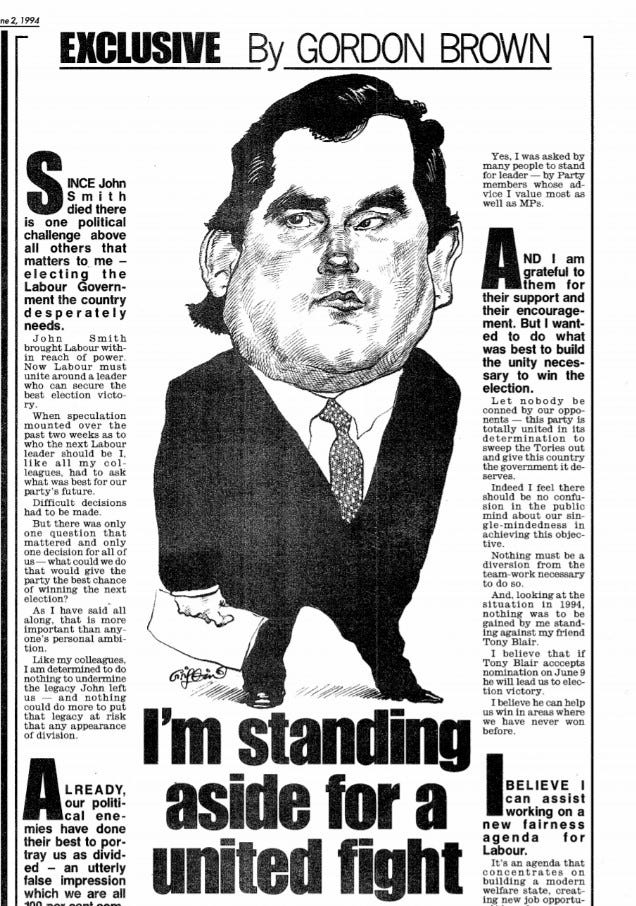

By the weekend, Gordon Brown had seen enough and was ready to put his own leadership ambitions on hold and support Blair’s candidacy. But he needed to devise a strategy for bowing out without losing face.

The strategy appears to have come together over a series of dinners, including two on the same night. On Monday, May 30, Brown had dinner with Charlie Whelan, his press secretary, and the MP Nick Brown at Joe Allen’s (a New York-style brasserie in Covent Garden).

The following day, he met Blair at the now infamous Granita meeting, where the pair confirmed the terms that had been agreed. That same evening, Brown raced over to the Rodin restaurant at Millbank, where he ate with supporters and made further plans for his retreat.

Brown needed to be seen to be withdrawing from a position of strength. On Monday, Mandelson tried to persuade lobby journalists that Brown’s support among the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) was actually level with Blair’s, a complete lie that no journalist could reasonably be expected to believe.

On Tuesday, while Blair and Brown met in Granita, Mandelson wrote up a “line to take” briefing to alert journalists that Brown would be throwing his full support behind his Labour colleague. The document went through several drafts throughout Tuesday night and Wednesday morning as Mandelson faxed a series of updated iterations from Hartlepool to the two men in London to scrutinise and quibble over. At one point, Mandelson’s fax machine broke, bringing the process to a hiatus while Steve Wallace, Mandelson’s aide, was sent to buy him a new one.

Brown wanted public assurances of the promise Blair had made, and he wanted them in no uncertain terms. In one draft, Brown crossed out a sentence that said Blair was “in full agreement” with Brown’s fairness agenda, and scribbled by hand on the page, “has guaranteed this will be pursued.” The process was brought to a close when Mandelson tipped journalists off at around 3pm.

As painful as it must have been, in standing down, Brown all but guaranteed Blair would become the next leader of the party by unifying support around a single modernising candidate. It was all over bar the shouting. He and Ed Balls would join the Blair campaign and provide regular advice on economic policy.

The new account is less romantic. The imagery of two young cardinals in the Islington conclave bargaining over the terms of Brown’s support for Blair’s leadership is certainly statelier than one man calling another for help with a jammed lavatory door.

Is that smoke coming from the kitchen?

What colour is it?

Looks black—oh wait, Ed Balls is holding a plate of smoked whitefish to the window! We have a new leader.

But, in a way, the real story is just as fitting. Yes, New Labour is the Granita of 1990s British politics—the trendy eatery redefining British Labour dishes for the modern electorate palate. But Gordon Brown had also been locked in the metaphorical shitter.

Timing is everything in politics, and Gordon Brown been handicapped for two years by being the responsible shadow chancellor. He had had to hold the party line on economic policy, push for increased financial discipline, and avoid overcommitting. Blair, on the other hand, had been free to take shots at the Conservative government’s record on law and order. Blair spent two years building his brand while Brown had been tied to building the party’s brand. Ultimately, this had left Brown in the Labour Party toilet, and when Smith died, he was still fumbling with the lock.

Before you go…

John Curtice analyses the latest polling for a ‘Swiss-style’ Brexit for UK in a Changing Europe.