Q & A with Sarah Baxter

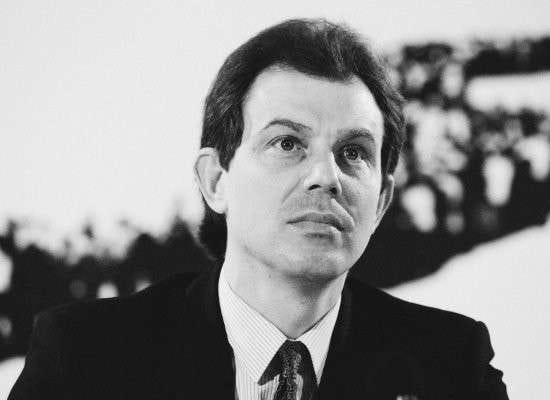

The former deputy editor of the Sunday Times discusses the media environment following Smith’s death, her notorious profile of Tony Blair, and why he led the pack.

Sarah Baxter, the former deputy editor of the Sunday Times, former political editor of the New Statesman, and now the Director of the Marie Colvin Center for International Reporting at Stony Brook University in New York, authored the first profile of Tony Blair after John Smith’s death. The piece in the London Evening Standard, “Why I Say Tony Blair Should Be the Next Labour Leader,” generated accusations from those close to Gordon Brown that it had been orchestrated by Blair’s spin doctors. She spoke to IFTC about how that profile came together, why Brown’s over-caution hurt his political career, and the needlessness of the Granita pact.

Who were you working for when John Smith died?

I was actually between jobs. I was about to go to the Sunday Times. I had left the New Statesman. My memory is I'd literally just landed back from South Africa, where Nelson Mandela had been elected.

I did a deal with the New Statesman that for my last month I'd go and cover the South African elections for them. My sister-in-law lived out there and my husband was a photographer, so I thought, let's do that. I worked out my notice covering Nelson Mandela's election, which was pretty incredible.

What is it like when an opposition leader dies unexpectedly? How do the media priorities change, particularly when that party is ahead in the polls, as Labour was at the time?

Labour was ahead in the polls, but rather as now with Keir Starmer, there wasn't that huge sense of confidence that they were definitely going to win. It was nice to be ahead, but they'd been out of power for so long it was hard to believe that when really tested in battle in a general election that they would win.

So when [Smith] dies, obviously the tributes pour in, but also everybody knew at the time that there was the potential for a seismic shift in the Labour Party. Everybody who reported on the Labour Party knew that there was a younger generation that couldn't wait to grab the reins and modernise it. So although his death came as a great shock and he was genuinely loved in the party, it also felt like a really important change and it was very important for Labour not to miss its moment.

Two years previously in 1992, Blair urged Brown to run and promised to support him as a leadership candidate. By 1994, the dynamic was different. The pair’s standing in the party was more level. You interviewed Tony Blair for the New Statesman a few months before Smith's death and you said in December 1993 that he was the likely next leader. What had changed between 1992 and 1994 that allowed Blair to step out of Brown’s shadow?

You are right to identify that piece in the New Statesman because that interview was still fairly fresh in my mind, and I definitely thought Tony Blair was the one after that.

What had changed is actually what now looks like a characteristic mistake by Gordon Brown, which is that although he was a powerful thinker, he never seized the moment properly. He should have run against John Smith and lost [in 1992]. Then he would have been the heir apparent.

He was already considered the brains and Tony Blair was considered the presentational shine on the gloss of the next generation. Not everybody understood quite how much depth and determination Blair had until later.

Brown felt like the senior figure and the intellect, but he missed his moment to be the next leader-in-waiting. He did it again when he didn't go for an election when he should have when he was prime minister. The polls were favourable but not as favourable as he wanted—he couldn't guarantee victory. He hesitated. He thought, "I better not do it". He walked everybody up to the hill and then walked them down again, and then, of course, he lost when he did call his general election later. We didn't realise it then, but it was a bit of a flaw in Gordon Brown.

I think Tony Blair knew after John Smith's death that this was his chance. So he grabbed it. There is a character difference between the two men there.

Blair's "tough on crime" [slogan] was very significant in Labour terms because it showed that he was prepared to sort of park his tanks on the Tories’ lawn.

Gordon Brown meantime was being Gordon Brown. He was being super responsible. You might even compare it now to what Sunak is doing. Gordon Brown had a reputation for being the Iron Shadow Chancellor, [saying] "we've got to be really financially disciplined. We're not going to make spending pledges that we can't live up to. We're not going to just borrow, borrow, borrow." Labour MPs don't like that message. It doesn't feel very exciting. It feels like they're in for quite a dour time. Tony Blair didn't have that.

Brown, being the senior person, also came in for quite a bit of incoming. He was unmarried. People are quite weird about that, about having an unmarried leader, particularly in the nineties.

They had had Ted Heath for the Tories. But Ted Heath had come in for quite a lot of stick over it. It came back to haunt him years later with phoney accusations of being a paedophile, which were completely concocted and stupid. But the fact that Gordon Brown was unmarried was perceived as a weakness. It wasn't anything that anybody said was a weakness publicly, but privately they discussed it.

[Tony Blair] just looked like the leader that Labour had been waiting for. To really seize the moment. Labour was in a good position already. John Smith had got them up that hill. He'd got them into a good position to win. He hadn't guaranteed victory. So somebody who was persuasive, articulate, intelligent, telegenic, like Tony Blair was ready to push it over the hill and win.

Then when Smith died it sounds like a briefing war erupted where Derek Draper and Peter Mandelson and the like rushed to secure favourable coverage for leadership contenders.

I know I'm in the history books as being briefed by those people. I knew Draper. Mandelson didn't like me very much and positively disliked me after my Standard article because he wanted to disassociate himself a bit.

[But] I had no dealings with him whatsoever. In fact, I didn't have time to have any briefings. I just wrote the piece.

I think I'd literally just flown in from South Africa. It was like eight o'clock in the morning, phone rings, it was actually Sarah Sands, who became producer of the Today program, she was the features editor. She said, "Sarah, can you write an appreciation of John Smith? We think he's dying."

Oh God. Okay. I start writing and then she rings again.

She says, "no, no, stop, stop. We're going to look at who might be the contenders. Can you write about Tony Blair? You've got an hour " or something.

So I write about Tony Blair. I bash it off the top of my head. I mean, I'm well informed, obviously, because I'm the political editor of the New Statesman. I slam out what I think of as a profile of Tony Blair. I definitely say he's going to be the next one and that Gordon Brown has problems. Robin Cook and John Prescott didn't thank me very much for just brushing them aside as having no hope whatsoever. It was all written very fast.

I didn't choose the headline. It's often the case with journalism, you don't choose your own headlines. I remember heading to Westminster as soon as I finished the piece. I thought I'd better get to Westminster and find out all the gossip. I stopped at the tube station opposite Westminster, picked up a Standard, looked at it and practically fainted when I saw it had a headline that said, "Why I Say Tony Blair Should be Labour's Next Leader," when John Smith had only been dead a few hours. People thought it was pretty tasteless.

The idea that I'd been briefed by anybody to say this was absolute nonsense. I'm assuming the Brown camp spread it because Paul Routledge, who wrote books about Mandelson and Gordon Brown, mentioned this twice and he was very close to Brown. But frankly, that [piece] had nothing to do with Peter Mandelson or Derek Draper, and I wasn't briefed by either of them.

Also, although I said it first, this was not surprising. It hit the Brown camp like a thunderclap. They hadn't quite realized how much things had moved away from them. It didn't particularly surprise anybody else. Even among the left of the party, people recognised that Blair was the guy who might be able do it. So I wasn't saying anything surprising.

The Brown camp was absolutely livid, but honestly it was not plotting. You didn't have to plot. You didn't have to be briefed. You didn't have to be told what was going on by Peter Mandelson or Derek Draper to know what was going on.

The one person I did ring was Anji Hunter. I rang Anji Hunter because I knew her, she was a much more friendly woman, and I felt I had to ring her to say, "is he running?"—because if he's not running, there's no point in writing about it. She said, "oh my God, Sarah, I can't believe you're asking this. It's far too early" and put the phone down. She's never forgotten that call. We laugh about it but there was no briefing.

I had been away for about a month in South Africa. Everything I wrote [in the Evening Standard piece] was baked in several months before. Blair had already won the soft left. that was crucial.

I think Gordon Brown wants to present Tony Blair as being much better at spinning than he was. He's the authentic real deal, and Tony Blair is just a spinner, and he had his spinning friends—whether it's Alastair Campbell or even, dare I say, me—out there spinning for him.

Whether it was wise to go in with both feet like that and jump into it within hours of John Smith's death, who knows? But I honestly felt I was just, as an honest reporter, painting an accurate picture of the situation as I saw it.

I was actually surprised that Tony Blair did the Granita deal with Gordon Brown, because I didn't think he needed to. He would've won on his own anyway. He would've won outright. I think [it was] to be kind to his friend; they'd come up together—who'd been a source of so many ideas. He didn't like to say to him, "look, it's completely over, mate. you lost." But that Granita pact led to a lot of splits and anguish for Blair for the next 10 years.

Do you think that Brown might have run if he hadn’t had assurances from Blair that he’d be in charge of economic and social policy?

He would've run and he would've got defeated.

Was there a risk of him splitting the moderniser vote and creating an opening for someone like John Prescott or Robin Cook to become leader?

Well, if you go back to my Evening Standard article where I said they had no chance—that remains my verdict.

Personally, I think that Blair would've won, Brown would've lost, or he would've not stood because he knew he'd lose. Then you wouldn't have had that terrible Blair-Brown psychodrama for the next decade.

I mean, Brown was constantly from that point on having drinks parties for backbenchers. He was always doing the hail-fellow-well-met with other Labour backbenchers throughout his chancellorship. He realized—fatally—he was very hardworking, very determined, a sort of public servant really, so bent on his plan, so determined to modernise Britain, so determined to win for Labour, get the economy right, that he hadn't been out there courting Labour MPs. He suddenly realised his mistake.

Before you go…

Sarah Baxter assesses why Kamala Harris’ popularity has been waning in the New Statesman.

Anthony Barnett argues the UK is a prison of nations following the Supreme Court’s ruling on a Scottish Referendum in Byline Times.

In a blog post for the Mile End Institute, David Ward assesses the parallels between the Conservatives’ strategy in 1992 and today and the tough choices facing Labour.

John Curtice analyses how Hunt and Sunak’s autumn statement will play with voters for the Independent.

Correction: A previous version of this newsletter misnamed Robin Cook as Robert Cook. Appalling that transcription software cannot yet recognise formidable former Foreign Secretaries when it hears them.