Q & A with Christian Wolmar

Britain’s leading rail commentator discusses privatisation, how Labour can fix the railways, and why the Queen should have been taken to London by train.

Christian Wolmar covered the privatisation of British Rail in the early 90s as a transport correspondent at the Independent. He has since written more than 1,500 articles and 20 books on transport and railway history, becoming one of Britain’s leading rail commentators. IFTC caught up with him to discuss the latest Tory plans to save Britain’s railways, Labour’s options, and why the Queen should have made her final journey by train.

His latest book, British Rail: A New History, was published this summer and is available for purchase.

This interview has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

What was the rationale for privatizing British Rail in 1993? Was it a solution in search of a problem? Or was British Rail genuinely in need of an upheaval?

No. There [are] really two railways. There's a commercial railway, which makes money and pays for itself and then there's a social railway that is necessary and will never actually pay its way but provides a very important link for various towns and cities. It's a national, and to some extent social, service.

There has to be an understanding between government and the railways about why it is subsidized, what its purpose is, and why it is basically an essential part of the social fabric in the way that schools, hospitals, and the army is.

British Rail had gone through some bad times. It had wasted a lot of money in the 1950s and early 60s on misplaced modernization schemes. But then it found its mojo.

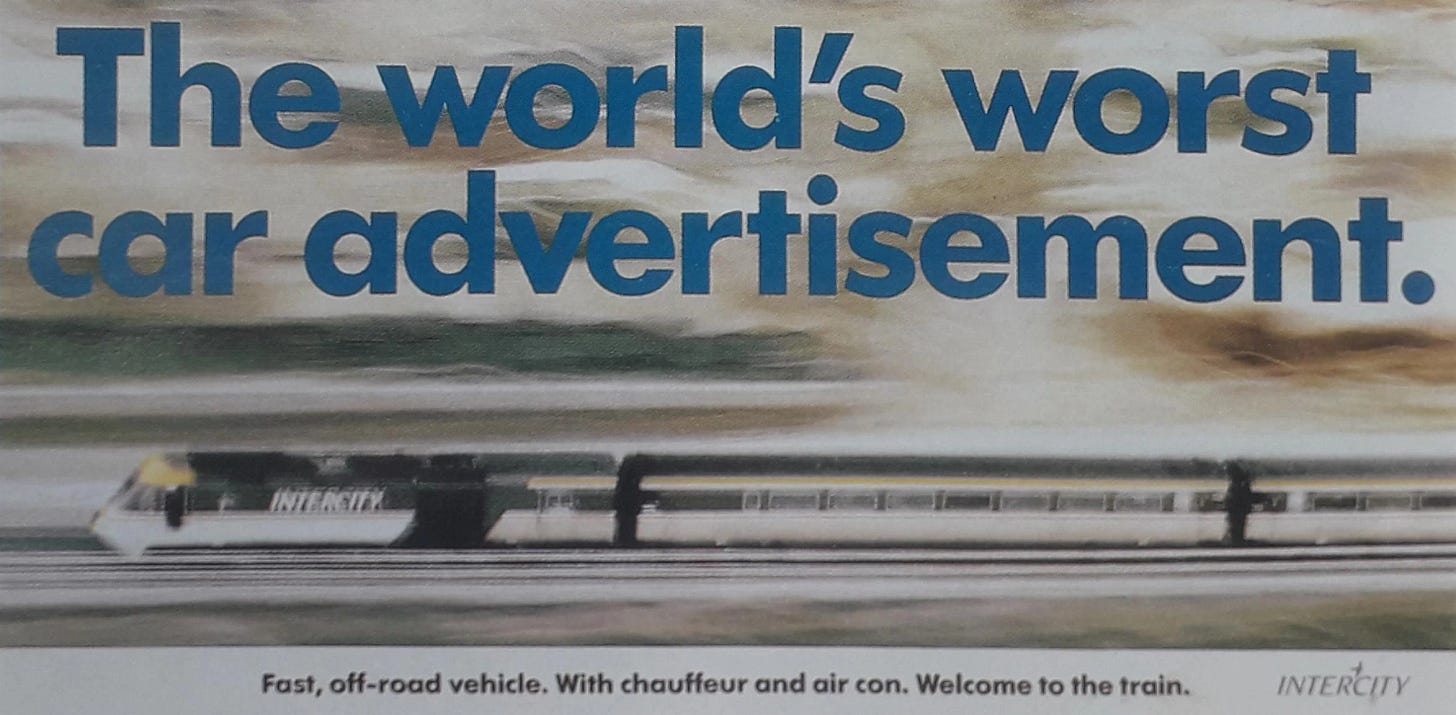

By the late eighties, it had created a structure involving three different passenger companies: InterCity, Network SouthEast, and Regional Railways. Regional Railways was the dumping ground for the loss-making services and obviously, it needed a lot of subsidy, but it did improve services. Network SouthEast amazingly broke even. InterCity was highly profitable. It had a nationally known brand with excellent advertising and marketing.

[Privatisation] was purely driven by an ideological imperative to involve the private sector to create competition, which is nonsensical on a railway.

The fundamental mistake in the way it was privatized was that they split the infrastructure from the operations. The infrastructure doesn't make any sense without the operations and vice versa. It is inherently an integrated business and that separation causes a lot of expense and hassle, and creates artificial capitalist constructs that don't really work.

The treasury was obsessed with the idea that you had to have a competition, and in order to have competition, you had to delineate each function.

I liked your line in the Sun earlier this year. You said, "it seems the only competition is to be the worst train operator."

By and large railways are a natural monopoly. So there's very little of what is called "open access".

There was a fundamental contradiction at the beginning of the whole process, which was that to get the franchises, [firms] had to bid for a certain amount of subsidy or they had to pay a premium to guarantee the use of a certain set of lines for 5, 6, 7 years or whatever.

Once you do that, the last thing in the world you want is for somebody to say, "we'll run an 8 am train and we'll run a 5 pm train. So we'll pinch all your customers and you won't be able to do anything about it." Of course, [the government] couldn't allow that.

So right from the beginning, they [privatised to] allow competition, [but] it was never feasible to actually have proper competition because any new entrants would've cherry-picked the profitable services and not operated the unprofitable services.

The notion that you could have unfettered competition had to be killed off at birth because if you were going to attract franchisees, they had to have a guarantee that they could run the bulk of the services—and certainly the profitable services—otherwise they wouldn't have entered the market. The whole thing was a nonsense.

It was [also] much more costly to run. The subsidy needed to run the system increased greatly from the amount being paid out to British Rail. A lot of the franchises went bust. Subsidy has remained at a higher level than the British Rail days throughout the whole history of privatization.

The Johnson government proposed the Williams-Shapps plan to fix Britain’s railways. Is this just franchising by another name?

Yes.

COVID completely wrecked the franchise model. It was [already] collapsing. There were fewer franchisees prepared to take revenue risk. Several of the individual [lines] were taken over by the government.

As we emerged from COVID, the idea was that there would no longer be the transfer of risk to the private companies—which was a fundamental part of privatization.

Private companies would be asked to run the services for a management contract fee of around 1 ½, maybe 2 percent of revenue, which they'll be able to keep. And if they run a certain number of trains on time, they'll get a bonus.

That is not entirely a daft idea, except that one of the motivations behind it was to make the whole [system] simpler. [But] incentives will [need someone to] check who is responsible for a train being on time or late or delayed or whatever. That returns us to the whole complexity of the system that Williams-Shapps are claiming they want to get away from because it's complicated and messy.

So unless there was total re-nationalization with government or a new state-owned organization taking all the risk for revenue, then we're just going to return to a system that will require lots of checks and balances and regulatory involvement and will be as complicated as what we've left.

We're about to head into party conference. Maybe we will soon have some clarification on what Labour’s policy towards Britain’s rail network will be, but what would you recommend to Keir Starmer?

When I talk to senior rail managers and people in the Department for Transport (DFT), they're very clear that there are two options.

You [can] do genuine privatization where you pass all the risk to private firms. You risk a whole lot of closures, as has happened in several countries, where the railway has effectively ceased to function as a national service.

Or you [can] have simple nationalization and revert to a British Rail—hopefully at arm’s length from the DFT, which is very important. You [could] create something like the British Railways Board with senior railway people involved. You give it a budget and you let them get on with it.

But what you don't do is set a whole lot of very detailed requirements and have lots of regulation and lots of people with fingers in the pie, because you'll end up with a structure that is just as complicated as it is today.

British Rail worked best when it had a good relationship with ministers and ministers allowed it to make decisions without day-to-day interference. You need politicians who are prepared to allow it to be on something of a long leash.

Imagine a scenario where Labour wins the next election and nationalises the rail network as you describe. Is there a way to insulate the rail system from the following prime minister re-privatising the network? Or will the railways always be at the mercy of those in Number 10?

In all my writings, I always stress that the railways are political. I've written about railways across the world and wherever you go, the railways are an arm of the state, even if they're privatized. Their fate is largely determined by government involvement of one sort or another. You can't really get away from the fact that big decisions are going to be made hand in hand with government.

If you have a government that is supportive of the railways and will listen to the voice of railway managers—experienced railway managers—and work in concert with them, that would be the best outcome.

It's difficult to see how it would be done in the next few years, but I remain optimistic that maybe Keir Starmer understands this and that if we get a Labour government, we might get a much better structure for the railways.

We are talking on the day of the Queens' funeral. I saw you recently made the argument that she should have been transported back from Scotland by train. Why?

The plan (under Operation London Bridge) had always been to take her by train— until a couple of years ago when the security bods and the safety bods somehow persuaded the palace that this was not a feasible idea and that it would be risky.

Why I don't think it would've been risky is that the railway lines are fenced in this country. The stations could've been risky, but you could easily police that.

In a way, it was the same with football. They cancelled football because they were worried that everybody was going to make a lot of noise and wouldn't respect the minute silence. I was at a football match where it was respected amazingly. The crowd was as silent as I've ever seen a crowd in one of these shows of mourning.

I think the same would've happened with the railways. People would've just stood at the platforms and watched the Queen go by. It would have enabled lots of people to have seen the Queen without having to go to London and without having to queue up. That was a great missed opportunity.

And we could have been spared all this social commentary on the queue, which would have been a bonus as well.

Before you go…

30 years after Black Wednesday, David Ward challenges the narrative of 1997 that credits modernization, targeting the political centre, and internal reform for Labour’s electoral victory and ignores the importance of the ERM crisis in this piece for the Mile End Institute.