Q & A with Anthony Barnett

The first director of Charter 88 discusses New Labour’s endorsement, then retreat, from constitutional reform, and why Brexit is a constitutional revolution.

IFTC spoke to Anthony Barnett, the first director of Charter 88 and founder of openDemocracy, about how Charter 88 built a popular movement for constitutional reform outside of traditional politics, New Labour’s missed opportunity to reset the relationship between the British public and state, and why any new attempt to rework the constitution would need to come from a grassroots movement.

This interview has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity. Anthony Barnett’s latest book, Taking Control: Humanity and America After Trump and the Pandemic, and documentary, US Progressives on a Knife Edge, are out now.

How did constitutional reform initially capture your interest and how did you become the first director of Charter 88?

AB:

I had applied for the New Statesman editorship in 1986 and was turned down. In part because then Labour leader Neil Kinnock backed John Lloyd, a Financial Times journalist, and opposed me. Both I and Lloyd have written about the episode. Lloyd, as he put it, made “a mess” of it. But while he was editor, they decided to make a supplement for the 20th anniversary of 1968 for the Christmas 1987 issue. Then Lloyd resigned and Stuart Weir became the editor.

Stuart is a very creative. He rang me up and said, “I’ve got this supplement on 1968, will you write an editorial on 1968?” I said, “the real anniversary is not 1968, it’s 1688,” the year of the so-called ‘Glorious Revolution’ that created the British state. He said, “write something about that.”

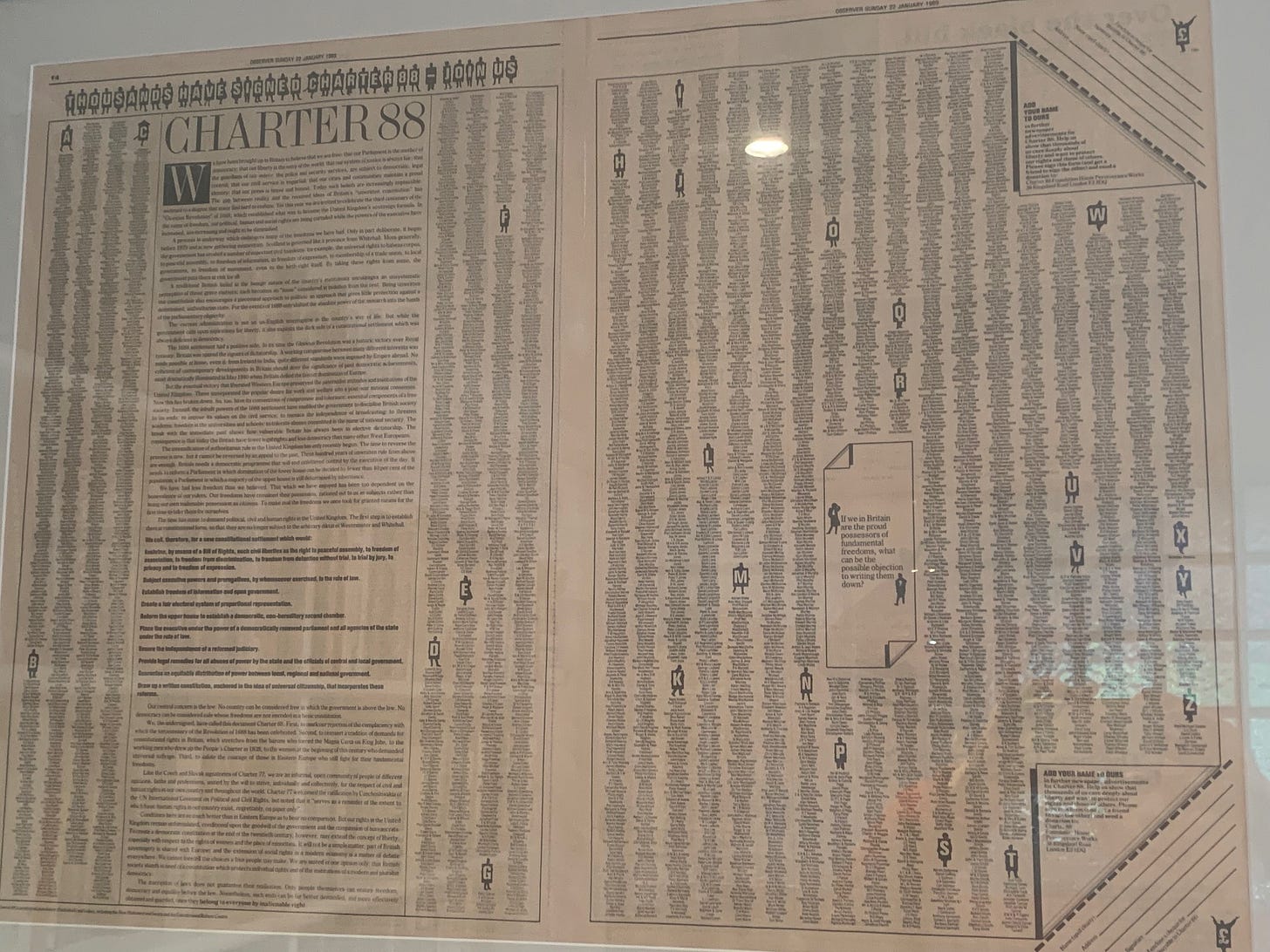

I mention this because in proposing how to make a success of the New Statesman, I’d argued in my application that making Britain a democracy was the issue that would bring in readers from left and centre against Thatcherism. After Thatcher won the 1987 general election the sense of “we need another way forward” really built. An American colleague said to Stuart Weir, in response to the editorial, why not call for a Charter 88, echoing Charter 77’s call for democracy and human rights. Stuart was looking for a way of rebranding the New Statesman and journalistically repositioning it. He decided that was a good idea.

The charter was drafted and re-drafted over nine months. Stuart ran the process and put together the alliance of signatures from Liberals to left-socialists, with no politicians, but many legal and cultural figures. I brought in writers such as Ian McEwan, John Berger, Angela Carter, Salman Rushdie, Marina Warner, many of whom had supported by application.

It took off and thousands signed and sent money. Only after that did Stuart make me the director.

The task was to turn a protest into a campaign and use the moment to create something lasting.

The important thing to understand is there was already a very active Campaign for Freedom of Information, a well-led Labour campaign for electoral reform, the pursuit of human rights around Liberty and especially the Scottish constitutional convention. The separate issues had advocates in a piecemeal way. Charter 88 brought them together into a unified call for overall political renewal and a new codified constitutional settlement.

It was also pro-European. One of the phrases I put into the Charter, which I’m proud of, is that “part of British sovereignty is shared with Europe”. Its ten demands were quite old-fashioned, classic constitutional ones, but it also looked to a new process to protect new rights and pluralism. It was pro-modern.

It was also cultural. It had writers, actors, filmmakers. The campaign was consciously [part of] civil society, of outsiders pushing for a different form of politics. It meant the politicians were annoyed and irritated by it, but it also meant it was much more interesting.

We then consciously connected it to new issues as they came up, whatever the issue of the day was; it might have been the war in Kuwait and the First Gulf War. I brought in one the best marketing experts. So we ensured that it was not routinised into a set of demands that everybody was familiar with.

The strategy document sent to all supporters made convincing Labour to back a Bill of Rights a priority along with making constitutional issues part of the next election. As we did not know when this would be, we planned what we called Democracy Day on the Thursday before the election, whenever that was. This would be organised by local groups. How we managed to make it legal was quite complicated, but there were 102 Democracy Day gatherings and we forced electoral reform into the national election debate, supported by the Liberal Democrats.

Kinnock was sympathetic but uncertain, while his deputy Roy Hattersley hated what we were doing. The result was that Labour acknowledged that the issues were important but was incoherent. This added to the last-minute collapse in support that swept John Major back into Downing Street.

Did Labour’s later endorsement of several of Charter 88’s demands under Tony Blair, while improving the feasibility of getting some things done, detract from the long-term objective of implementing a constitution that is not vulnerable to party politics?

AB:

That is a very good question. Gordon Brown understood that you needed to empower people to make the state accountable to the citizen. He understood that as a core issue before 1992, and said so in his Charter 88 Sovereignty Lecture. John Smith became leader after the 1992 defeat and committed Labour to enacting a Human Rights Act as well as a Scottish parliament in his Charter 88 lecture. He wanted to make parliament accountable, but he was not ‘New Labour’.

What Blair and Brown saw was a historic need to modernise the Labour ‘project’. They saw a proletarian party as doomed and perceived a need to embrace the market—in effect to replace internationalism with globalization. Globalization would generate jobs and income and growth for all.

Brown always remained committed to looking after the poor. Blair didn’t give a damn about the poor, to be frank.

Brown also understood the need for constitutional issues to provide a new ‘national story’. But in the agreement between them, [the Granita Pact], Blair got the constitution and the international and social agenda—Brown the economy.

Blair, Peter Mandelson, and their press secretary Alastair Campbell wanted power and disliked all this democracy stuff. They decided that Blair had to implement what he was committed to—a Human Rights Act, Scottish Parliament, Welsh Assembly, Freedom of Information, abolishing hereditary peers—but he didn’t believe in them and refused to integrate them into a new overall settlement. In this sense, as your question implies, the core demand of Charter 88 was rejected.

More than that, Blair set about a process that was partly instinctive to use constitutional reform to break the old system and culture, but not to replace it. A key moment we only found out about much later was in 1997. When he had his first cabinet meeting, two ministers raised issues of the day. After the meeting, he summoned Robin Butler, his head of the civil service, and Jonathan Powell, his chief of staff, and asked what was going on. Butler said, “we have a cabinet government.” Blair shook his head—I have this on first-hand account—and said it is not going to happen again. Butler had to ring up every ministerial department and say, “nothing is to be raised in cabinet without the prior approval of the prime minister.”

If you are the director of a board and you are told, “you’re not allowed to raise an issue unless the chief executive permits you” then you become prisoner of the executive. In effect, cabinet government was replaced by prime ministerial authority, in this case with Brown acting autonomously at the Treasury.

It was an enormous defeat for democracy.

The tragedy is that they managed to fix the media—supported by Murdoch—so there was never a proper debate or discussion of what happened at the time, and the Lib Dems just caved as they were sucked into a promise of electoral reform that evaporated.

This wasn’t just a passive process. If a journalist raised a constitutional issue, Alastair Campbell would say, “fucking constitution! Who gives a fuck about the fucking constitution!” and the journalist would just cave. The Blair government delivered an incredibly radical set of reforms yet made constitutional issues unimportant.

In the current context of renewed calls for Scottish independence, tentative Labour-Lib Dem cooperation, Brexit, and the Northern Ireland protocol, are we approaching a moment of far more ambitious and extensive constitutional reform?

AB:

We have just had ambitious constitutional reform. It was called Brexit. I have spent half a lifetime, since 1988, being told by Labour politicians that no one is interested in the constitution on the doorstep, and that voters are only interested in potholes or jobs and schools and welfare. Then 52 percent of the British electorate, and a much higher majority of the English electorate, voted to “take back control”.

Taking back control is a quintessential constitutional demand. It is about process, it is about who governs, it is about who should be in charge. And because it is about power, it is immensely popular.

So we are now in our constitutional revolution. There is no way out of it.

The other thing I’d say is that New Labour was the last moment when the population would have accepted a new settlement being offered by the government, because the end of the nineties was a moment for a ‘New Britain’. There could have been a moment of rebirth organised by a Labour leadership that was young, intelligent, smart, and had legitimacy. You hadn’t yet had the Iraq War, the war on terror, the financial crash.

Now, the entire governing order has deservedly lost popular trust. That, plus the internet, means reform [of] the constitution demands a new process of participative democratic legitimacy. You have to have a citizens-based process. For a governing party to just present a new constitution to parliament would not be acceptable. You couldn’t do it anymore.

I don’t want to be too pessimistic. There is an understanding of the need for wholesale change. But I would warn against any idea that any particular reform can mechanically lead to a new settlement. A profound cultural shift is needed. It is already happening across the public. How long it will take for the political class to catch up is unclear.