Newbury punters shun Tory runners but won’t bet big on Labour

The 1993 local elections and a by-election in Newbury showed that although the British public had lost patience with the Tory government, Labour still had work to do.

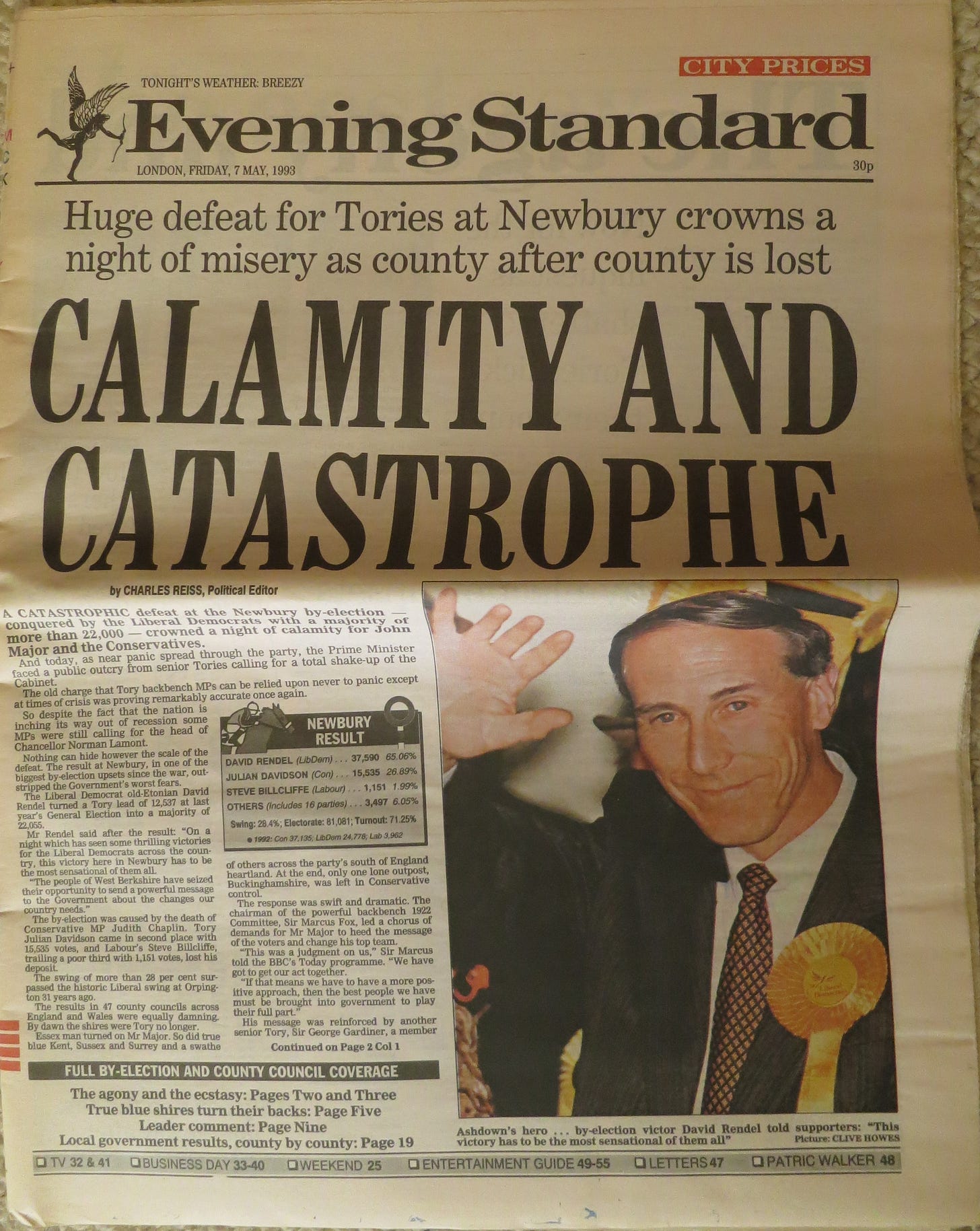

The Conservative party took two stinging electoral blows in May 1993. In a single week, the party lost control of 15 of its 16 controlled county councils and lost a Commons seat in Newbury’s by-election, prominently rebuffing John Major’s government just a year after his general election victory.

When the local election results from all 47 county councils in England and Wales had been counted, the Tories had lost 429 seats, surrendering control of their Kent and Surrey heartlands. But, while Labour now held the most counties with 14, the Liberal Democrats were the week’s winners, gaining 341 seats to Labour’s 78.

John Major’s first electoral test had not gone his way. But nor had it gone Labour’s. Labour’s urban strongholds were not voting in 1993, but, while Labour claimed to be the party of local government, its poor showing in the South and the fact that 27 county councils still had no single party in overall control demonstrated that voters weren’t ready to embrace Labour without reservation.

The same day, in the Newbury by-election—triggered by the death of Conservative MP Judith Chaplin—the Liberal Democrat David Rendel ousted the Conservative incumbent with 65 percent of the vote, trimming the Conservative Commons majority to 19.

For what went wrong for the Tories in the local elections, look to Newbury

The Major government had made some headway with inflation, dragging it down from 3.8 percent when he entered office to 1.8 percent in 1993—the lowest rate in Europe. But it had come at a high cost for British families.

Inflation-fighting policies, like interest rate hikes and spending cuts, had taken a toll on employment. Unemployment climbed from 2.7 million in 1992 to over 3 million in February 1993 and, although it had fallen slightly since, still stood at 2.9 million when voters went to the polls in May—around 11 percent of the workforce.

Newbury typified Thatcher’s boom and bust. The traditionally prosperous constituency had returned a Tory MP uninterrupted for the previous 70 years. But the economic downturn was hitting the town hard. 130 businesses went bankrupt in 1992 alone, contributing to 4,000 unemployed. House prices had fallen by 40 percent since 1988, creating a “negative equity” town, where residents who had bought property under Margaret Thatcher now owed mortgages on homes worth significantly less. The Tory heartlands were littered with towns like Newbury

“Newbury, at the heart of the horse-racing industry, is the perfect town to pass judgement on John Major, whose economic recovery has had more false starts than the Grand National.”—John Williams, the Daily Mirror, May 4, 1993.

The Conservatives had also reneged on its 1992 general election promise not to raise taxes. A core campaign attack line in the 1992 election had been that a Labour government under Kinnock would be a government of high taxation. They Conservatives deployed the same line in the localities, that a Labour council meant higher council tax

.Yet, in the March budget, just weeks before the local elections and Newbury by-election, Chancellor Norman Lamont announced VAT would be added to domestic fuel for the first time and outlined plans to increase the rate of National Insurance from 9 to 10 percent, enfeebling one of their most prominent attacks.

If there was a league table for cabinet ministers, they’d be “some way down the Arthur Daley double glazing and patio window league for broken down semi-professionals.”—John Smith.

Voters didn’t trot into the Labour paddock

When applied to a general election, the 1993 voting patterns would have returned a Labour majority of 87. With more than half of the counties in England and Wales now returning hung councils, the elections had not been an enthusiastic endorsement of Labour. Fears that Labour couldn’t win in the South had not been calmed, and the opposition to the Tories remained split.

The Newbury by-election was never a target for Labour. Labour received just 6 percent of the vote in the 1992 general election. Peter Mandelson ran the by-election campaign, and not even his mastery of the dark arts of public relations could resurrect the dead. Steve Bilcliffe, the Labour candidate, lost his deposit with just 2 percent of the vote, in what was the party’s worst performance in any parliamentary election since 1918.

Mandelson’s biggest contribution was in building a plausible narrative for the inevitable defeat: “Labour had shaken the tree, but the fruit fell into the hands of the Liberal Democrats.”

But he had, in Newbury, accepted a basis for anti-Tory cooperation. His approach to Lib Dem candidate, Eton alumni David Rendel, was more measured than his treatment of Lib Dem candidates in by-elections the following year, and was happy to let tactical voting help oust the Tory incumbent. This broke with the local election strategy as, besides occasional Labour and Lib Dem decisions to stand down in Berkshire, Oxfordshire, and Wiltshire, both parties fielded more local election candidates than ever before.

Newbury was a hopeless case and, and, as Simon Jenkins put it in the Times, the Liberal Democrats were the “natural dustbin for protest votes.” The lukewarm performance was not cause for panic. The party was still years out from a general election. John Smith had plenty of time to position the party as a home for the anti-Tory vote and secure a victory.

At the same time, Labour couldn’t be complacent. Disgruntled Tory supporters willing to bloody the government in a local or by-election could still balk at helping Labour into Number 10. And with the Liberal Democrats polling at their highest rate in six years, a deeply divided opposition gave no guarantees in 1993 that Labour would be able to corral enough voters into the paddock to secure a majority come 1997.

Jill Sherman writing in the Times, captured the ground Smith needed to make up—beginning with raising his national profile. After witnessing Smith campaigning at Newbury’s Kennet shopping centre at the end of April, she wrote: “at least one shopper shook his hand without knowing who he was, while another said nostalgically: ‘There's the old Liberal leader.’"

The loss of county councils in the heartlands was troublesome for the Tories, but at this stage of the election cycle the Tories might have thought they could clip a few fences as long as the mare responded well to the crop in the last few furlongs of hard riding. But when they woke up in 1997, with John Major face down in the mud, wondering where it all went wrong, the fences of Newbury and the local elections of 1993 was one place where it looked like the nag was starting to falter.