Narrative problems and opportunities

The Blair campaign capitalised on the heightened attention of the leadership campaign to establish his political identity and communicate his vision—a contrast to the current Labour leader.

Labour’s weaknesses less than two years out from a general election are more evident in conversations with Keir Starmer’s supporters than his detractors.

“Keir Starmer’s great, yeah. Fantastic,” said one donning a double-breasted coat and beanie combo in a Novara Media video published in mid-December. As Ash Sarkar struggled to keep a cardboard cut out of the Labour leader from buckling in the Peckham breeze, she asked passers-by what he could offer the British electorate.

“He seems like a steady, reasonable person. He seems like he’s very focused on winning the next general election.”

A dogged focus on winning the next election isn’t an argument for why Starmer and why now. It isn’t a political story. It isn’t a flagship policy, a governing philosophy, or an element of a Starmer’s vision for Britain.

Almost three years into Starmer’s leadership, voters remain unsure of what he stands for beyond opposing the Conservatives and vague notions of electability. He’s struggled to establish a firm political identity. The party still holds a lead in the polls, but without a captain holding a political compass, any future Labour government’s appeal will rely on Tory seas remaining unimposing.

Starmer’s failings can be traced in no small part to the squandered opportunities of his leadership election. Whatever your views on Blair’s vision, it was unmistakably clear from the off, and he never deviated. Blair understood the importance of the first impression in politics. His team seized on the increased media attention of a leadership campaign to amplify his political messaging and show the electorate who he was and his aspirations for Britain.

Starmer’s pitch to the Labour membership in 2019 may have been what they wanted to hear, but it wasn’t a product of his own political creed. He campaigned for the Labour leadership on 10 pledges that courted Corbynites, Remainers, and elements of the left, with a promise not to “trash the last four years” of Jeremey Corbyn’s leadership. Since winning the leadership, however, he has abandoned many of the pledges, expunged Corbyn from the party, driven many members on the left out with him, and changed the party’s leadership rules to prevent the left from fielding future candidates.

Whether Machievellian (as the New Left Review’s Oliver Eagleton argues) or mercurial, Starmer’s rebuttal of his own leadership campaign has left a vacuum in place of a governing philosophy and fostered the impression of a political shape-shifter, leaving question marks over his sincerity, his commitment to a set of political values, and what policies could be adopted or dropped on entering Downing Street.

Blair acted quickly to prevent others from defining him

On June 2, 1994, the day after Gordon Brown publicly ruled himself out of the leadership race, political consultant Philip Gould wrote a memo to the Blair campaign explaining the need to establish Blair’s political identity.

Blair enjoyed warm coverage from the Murdoch empire, but Gould worried that the nickname Bambi, the moniker some in the media had given him to draw attention to his political inexperience, would quickly stick if the campaign couldn’t offer up an alternate identity. “It can either be the agent of change and renewal or the combination of Bambi and Bimbo the media is trying to create,” he wrote.

Blair followed up with a memo of his own outlining his themes for the campaign. On a personal front, he wanted to reiterate his Christian socialism and his introduction to the party through belief, not political inheritance or habit.

In a section entitled ‘Policy Framework’ he wrote that “individuals prosper best within a strong society—one nation socialism—but do it for a modern world,” and listed a series of policy directions:

Recreate the terms of community and social cohesion based on welfare, but with a self-improvement focus so as to avoid fostering dependence.

Economic regeneration through investment.

A skills revolution.

A new constitutional settlement between the society and the individual, including devolved power and individual rights.

Leadership in Europe and reshaping European cooperation.

A pluralist, open and inclusive brand of politics.

Transform the party towards campaigning and mass membership.

The memo now serves as a reminder of Blair’s consistency of ideas. The embryos for many of the policies that came to define his time in office—from the New Deal on jobs, Sure Start, devolution, the Minimum Wage Act, and the Human Rights Act—are visible in the memo. The document provided a lodestar for the campaign and set a course for policies, political style, and messaging.

They were not necessarily novel ideas. They had been kicking around think tanks, academic circles, the commentariat, business circles, and the Clinton campaign for some time. But Blair assembled them to create a coherent narrative that aligned with his own political leanings.

The communication challenge was articulating this narrative in a way that cut-through the political noise.

Show me the vision

“The media want a beauty contest… The media want a nice, cuddly, telegenic family man. Tony Blair must give them an uncompromising champion of change.”—Philip Gould in a June 10 memo to Tony Blair, Peter Mandelson, and Mo Mowlam.

Tony Blair announced his candidacy on June 11 at Trimdom Labour Club in his Sedgefield constituency. The backbone of his communication was a campaign document, Change and Renewal, and several key policy speeches: on education (on which David Miliband worked), constitutional change (Derry Irvine), the economy (Gordon Brown, Andrew Smith, and David Miliband), and welfare (Peter Hyman).

On June 23, he launched his Change and Renewal document with a speech that pulled all his political ideals together publicly for the first time in an articulation of his overall vision for the country.

He attacked the Tory government, outlining how the Thatcher and Major governments had frayed the social fabric of the country. “They saw all forms of social co-operation as inherently wrong, fit not for reform but for demolition,” a view, he called, “narrow,” “selfish, and ultimately self-defeating.”

There was a section that explained the heart of Blairist thought—“individuals prosper best within a strong, active society, whose members acknowledge that they owe duties to each other as well as themselves.”

The theme of the speech was one of rebuilding relationships: between the individual and society, the worker and employer, and the public and the private sector. He reiterated the idea of education as underpinning these relationships, saying education “holds the key, not just to personal fulfilment, but also to economic prosperity and a good society.”

When asked how he would fund reforms, he refused to be drawn into writing Labour’s budget before securing power, but promised proper costings would be provided should the time come.

Blair recommitted to the pursuit of full employment, a minimum wage, and progressive taxation and, while the speech was exceptionally thin on policy, it served its purpose, which was to effectively communicate the core of Blair’s political identity. Of course, this was a luxury Blair could afford because of his opponents.

None of Blair’s opponents were incompatible with his platform

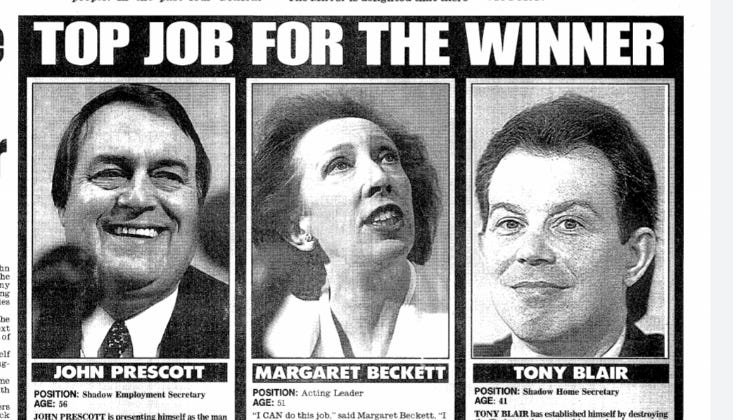

Both of Blair’s leadership opponents, John Prescott and Margaret Beckett, challenged him from the left. But neither were from the ranks of the economic disruptors.

John Prescott appealed to the party’s old guard, with an animated, no-nonsense political style. He launched his campaign at a miners’ picnic in Ashington, where he delivered a speech that brayed for a return to dignity for the unemployed and working class and reiterated the need to tax the rich.

Beckett’s political style was closer to Blair’s, although her policies clashed more with his own—particularly her calls to strengthen union rights—but were not incompatible.

The overlap in their agendas were apparent during a three-way Panorama debate where John Prescott remarked that the candidates were “going to love each other to death,” and the strongest disagreement surrounded what the target unemployment rate should be.

Blair almost certainly would have been drawn into more contentious policy debates had a member of the party’s left been able to stand. Ken Livingstone wanted to run, but fell 8 MP nominations shy of the threshold to get on the ballot. Without a economic populist candidate to challenge him over policy, Blair could afford to remain policy-lite and focus on using his exposure to develop his big ideas and political vision.

“He is eternally youthful, pleasantly earnest, capable of singing a catchy refrain, but not necessarily with much substance . . . I think he is the Labour Party's answer to Cliff Richard. Unlike Cliff he has failed to get into the charts”—Charles Wardle, Under- Secretary at the Home Office

Blair won handsomely

Blair won the leadership easily with 57 percent of the overall vote and won majority support in every section of the new electoral college, securing more than 60 percent of MP votes, 58 percent of the constituency votes, and 52 percent of affiliated organisations.

In the deputy leadership contest, a much closer race, John Prescott edged out Margaret Beckett with 56.5 percent of the overall vote to her 43.5 percent. Like Blair in the leadership race, Prescott carried all three sections of the electoral college.

Starmer undermined his own political story

Keir Starmer faced a unique set of challenges in the 2020 Labour leadership contest. The ballot was held in the early days of the pandemic, he stood in a crowded field in which five MPs secured the nominations necessary to progress to the second round, and in Rebecca Long-Bailey, he faced a genuine left-wing challenger in the final ballot. And he made a compelling argument for his candidacy that acknowledged the merits of Corbynism, warned against the dangers of unbridled marketisation, and touted a more human-centred approach to Europe.

By walking back his own ten pledges and rejecting elements of his own leadership campaign, however, Starmer has muddied the narrative of his own story. It has left him without a fixed governing philosophy on which to craft policy, deploy soundbites, and provide a coherent alternative to Britain’s current economic and social ailments. Without an underlying philosophy, policies risk sounding haphazard and forgettable, soundbites like posturing, and complaints like political point scoring.

Starmer will probably be the next prime minister, but the best leaders come with a compelling story of why them, why now, and what’s next, and Starmer’s shedding of his leaves him exposed.