Can Starmer revive Brown's pensioner army?

Older voters, a pillar of the Conservative base, helped Labour derail the Major government’s VAT hike on energy in the winter of 1994; Sunak cannot take their support for granted either.

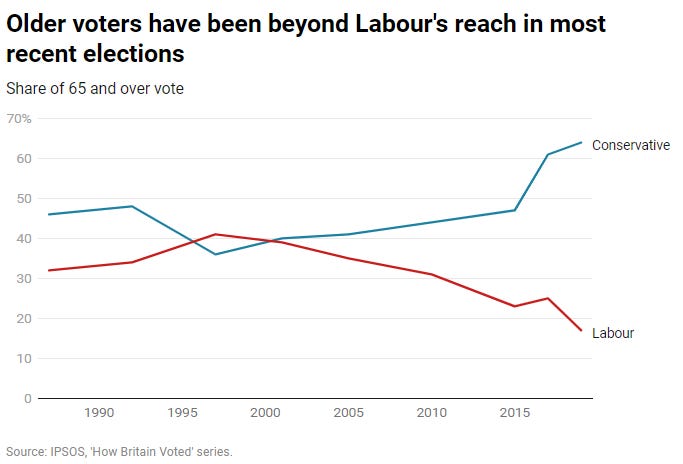

It’s no secret that Tory candidates in the ballot box, like an oversized bag of Werther’s tantalisingly close to the supermarket checkout, are a magnet for pensioners. These older voters are a central pillar of the Conservative vote with the “crossover point”—the age at which voters go from being statistically more likely to vote Labour to voting Conservative—clearly discernible in election data.

Their support, however, cannot be taken for granted. John Major’s Conservative government made that mistake in the early 1990s and paid for it in 1997—when Labour’s vote among over 65s exceeded the Conservatives’ for the first and only time in recent history. An army of older voters amassed to derail Lamont and Clarke’s VAT increases on energy bills. There are signs that this army’s allegiances may be softening, and that silver-topped column could yet turn on its generals.

Energy, like the biblical grain of mustard seed, will move mountains

While technically no longer in a recession, the UK economy was on shaky ground in March 1993. Growth had been slow since the late 1980s. The economy had contracted in 1991 and saw just 0.4 percent growth in 1992. Unemployment surged to more than 10 percent, depressing tax revenues and leaving millions newly reliant on the social safety net.

The UK’s public sector spending faced a borrowing requirement of £35 billion in the 1992-3 financial year and was set to climb to £50 billion the following year. Financial markets were spooked, and the pound was in free fall, reaching its lowest ever value by early March.

The Treasury sought to stem the economic haemorrhage and restore public confidence with its March 1993 budget, Norman Lamont’s first since the calamitous Black Wednesday.

Lamont outlined a raft of direct and indirect tax increases that would claw back more than £10 billion from the UK electorate. The bulk of the revenue was to come from National Insurance increases and the scaling back of income tax allowances, but the budget also included a proposal to introduce VAT on domestic fuel, which had been zero-rated since the introduction of VAT in 1973. The proposals would see VAT rise to 8 percent in 1994 and 17.5 percent in 1995.

Major knew the plan would be unpopular. Energy is a relatively inelastic good—people aren’t able to dramatically cut back on their use when prices rise (as we’ve seen in during recent price spikes)—making it an efficient way to raise revenues through a value-added tax, but putting the heaviest financial burden on the poorest and most vulnerable. The prime minister had also promised there were “no plans” to extend VAT in the run up to the 1992 election, lending the proposals the sting of betrayal.

Major initially rejected the idea privately but relented once the alternative proposal was revealed: to introduce a new, low rate of VAT on a host of other products previously exempt. He calculated that the backlash might be more manageable if the VAT hike was limited to energy, and the “wedge” of tax hikes could be taped down before the 1997 election.

Smith and Brown raise an army

Labour Leader John Smith and Shadow Chancellor Gordon Brown assailed the Major government for turning to a regressive tax like VAT raise revenue, highlighting the plight of the poorest who would be squeezed tightest. They found they had some unlikely and influential allies, including Margaret Thatcher, who maintained taxes shouldn’t rise, and One Foot in the Grave star Richard Wilson, who became an avid campaigner.

It was pensioners, however, who mounted the fiercest charge. In October 1993, a “pensioners army” protested the VAT rise at Westminster.

Norman Lamont had resigned as Chancellor after a humiliating by-election defeat at Newbury in May 1993, but his successor, Kenneth Clarke was equally committed to the tax rises. In the November 1993 budget, he went even further, adding fiscal measures to raise another £5 billion the following financial year, including freezing some personal tax allowances. Between them, the two 1993 budgets amounted to the largest peacetime tax increases Britain had ever seen.

“In one respect, however, the Government have proved consistent, and did so again yesterday. When in trouble they go for the vulnerable, and yesterday's Budget is no exception.”—Lord Richard, December 1, 1993, House of Lords.

Clarke had tried to placate UK pensioners by outlining the first above-inflation increase to the state pension since the 1970s, but the move barely offset half of the added energy costs pensioners would soon face and did little to quell discontent.

One vote cannot rule them all

Parliament passed the VAT hikes in the Finance Act of 1993 and the Major government assumed that was the end of the matter. The VAT increase entered law, with the first 8 percent rise due to apply to energy bills in April 1994, and the 17.5 percent rise coming into effect automatically the following year.

There were, however, signs that elements of Major’s parliamentary backers weren’t fully behind the measure. The nine Ulster Unionist MPs, normally staunch Tory allies, signalled their opposition to the 17.5 percent increase. Without them, Major’s majority of 14 suddenly looked very precarious.

In 1994, Nick Brown, Labour MP for Newcastle upon Tyne East and Brown’s unofficial campaign manager in his failed bid for the leadership, devised a legislative manoeuvre to force a new vote on the second VAT rise—the one that would raise the rate to 17.5 percent. He pushed for Labour to introduce a Budget resolution to the November 1994 budget debate, forcing a fresh vote on the second rise, yet to come into effect.

Meanwhile, the pensioner army continued to ensure the issue stayed in the news. In the run up to the winter of 1994, Help the Aged ran ads highlighting the dilemma many pensioners now faced: having to choose between heating and eating their homes.

Gordon Brown was also able to effectively tie the VAT hike into the broader narrative he was weaving about Tory Fat Cats and the executives that were getting rich on newly privatized utilities. Brown proposed an alternative source of revenue: ending tax breaks on executive share options.

Force the low tax party to make the case for higher tax

To win the new vote, Labour needed to peel off at least 5 Tory MPs. Reports were swirling that some might be willing to face down Kenneth Clarke and John Major, with several planning to abstain.

Labour would use Tory MPs’ own words against them. Chris Leslie, a young researcher who would eventually rise to become Shadow Chancellor in 2015, was tasked with going through local manifestos and finding Tory MPs who had made specific pledges not to raise VAT in their campaigns. At least nine had publicly opposed the principle of VAT, and every time they stood up to ask a question in Parliament, Labour assailed them with their broken promises.

The strategy was highly effective. Kenneth Clarke countered by arguing that nobody should take seriously promises made in a hustings “on a wet Wednesday night in Dudley.” But the public did. For many—especially over-50s, who dominate participation in local politics—those wet hustings in Dudley are drivers of civic engagement. Belittling them was tantamount to belittling British representative democracy and the principle that politicians hold office to represent, and are accountable to, their constituents.

Sensing some of his MPs were in a bind, and concerned the government could face an embarrassing defeat on the Budget resolution, Clarke outlined provisions in the November budget designed to court pensioners and rout the army.

Older voters were promised £1 a week (£1.40 for couples) off their energy bills, a £2.50 increase in cold weather payments, and £10 million in extra home insulation grants; the Daily Mirror was quick to point out the measure would still leave pensioners 77p a week worse off on average than they had been before the VAT hikes.

In a dramatic December 1994 vote, Labour’s Budget resolution passed 319 to 311, giving Labour candidates important ammunition to take into 1997. They could argue that Labour was the only party which had delivered a major tax cut in the 1992-7 parliament by reversing the impending hike and fighting to keep VAT on energy bills at the 8 percent level.

In 1997, Labour campaigned on a promise to cut VAT on energy to 5 percent, the minimum allowed under EU regulations, a line that clearly resonated with older voters.

Older voters could have a small, but important role in the next election

The 1997 election was a blip in the historical trend, driven more by pensioners’ desertion of the Tories than zeal for Labour. But, while it may seem insane to suggest older voters could be in play for Labour at the next election, given Labour’s unpopularity among the cohort in 2019, Keir Starmer may be able to raise a pensioner army of his own.

Replicating Blair’s share of more than 40 percent of over 65 votes isn’t feasible. But Starmer doesn’t need a horde to win the election.

Coastal towns in England and Wales, with their disproportionate share of older voters and homeowners, have been a reliable bellwether of older voter behaviour in recent elections. In every election since 2005, the Conservatives have increased their vote share in these seats, with Labour winning their smallest ever share of coastal towns in the 2019 election.

But polling from the Fabian Society carried out in November now has Labour winning in many of these seats. 38 percent of respondents in coastal town constituencies said they would vote Labour at the next election, the highest level since 2005. Among over 55s, Labour increased its support from the 2019 election by 7 percentage points, while Tory support slipped by 17.

Labour’s support is shaky. A lower share of voters in coastal towns believe Labour understands them than voters nationally, and support among older voters lags the British average. Hunt’s recent budget also announced a huge boost to the amount high earners can put away for retirement that could court over 55s.

But inhabitants of Britain’s towns are less likely to be among the highest earners. They hold university degrees at a rate below the national average. And even if coastal voters aren’t sure if Labour understands them, far fewer believe Rishi Sunak’s Conservatives get them.

There are also new signs that Sunak’s government realises it cannot take the older vote for granted as a proposal from the Treasury to raise the UK state pension age to 68 was recently shelved.

At least 30 coastal town constituencies are among the 125 most marginal seats in England and Wales, and if support proves resilient, Labour could win them and more and make significant inroads among a demographic that has been largely lost to the party since 1997. Labour estimates it would need to win 124 new seats in the next election, although that figure may be an undercount. Older voters, particularly in coastal towns, could form an important part of the election story if they rally under a new banner.

Before you go…

Apologies for the hiatus. I have been buried under Master’s work, but this will hopefully have been an anomaly.

Sarah Baxter joined 9 political editors and writers on the New Statesman podcast this week to reflect on their time at the magazine.

Sir John Curtice discussed how the Tories are “stuffed” in a New Statesman interview.

Christian Wolmar wrote about the revival of the sleeper train in the Spectator.