Bill Clinton to the rescue?

Bill Clinton’s victory in the 1992 US presidential election gave progressives cause for celebration—naturally Labour turned it into an internal argument.

On November 3, 1992, the charismatic governor of Arkansas secured a large electoral college win to retake the White House for the US Democratic Party after 12 years of Republican control. Bill Clinton and his brand of New Democrats broadened the coalition, reorienting the Democratic base away from organised labour and the working class to more affluent knowledge workers and suburbanites. They railed against the oversize power of special interest groups that they argued had limited the party’s electoral success prevented economic stimulus. They blamed President George H. W. Bush and the Republican Party for widening inequality and promoted a vision of a leaner government that better supported the market and deployed microeconomic and community solutions to macroeconomic issues.

It was cause for celebration for progressives across the world—or at least it should have been. Inside the Labour Party, however, once the initial triumph had passed, Clinton’s victory ignited a new conflict over what aspects of his platform and strategy could and should be replicated in UK politics.

How much of a road map to victory could Clinton’s Democrats offer Labour?

There had been substantial cooperation between the Clinton campaign and the Labour Party of 1992. Philip Gould, a Labour strategy and polling adviser for the 1987 and 1992 general elections, spent four weeks in Little Rock advising the Clinton-Gore campaign. Yvette Cooper, who worked in John Smith’s office, volunteered at the Clinton campaign HQ in the run up to the November election; Margaret Beckett had also spent time in the US after Labour’s 1992 election defeat.

After Clinton’s victory, Smith and others in the party took a deep interest in the elements of the US campaign that could be applied to future UK elections. Gould co-authored an essay on the lessons he took from the Clinton campaign, John Braggins, a senior Labour organisational officer, compiled a briefing for the National Executive Committee that was based on Yvette Cooper and others’ experiences, and David Ward, Labour Leader John Smith’s head of policy, wrote a paper on the key themes of Clinton’s policy platform.

There were some policy lessons to be learned, for example, the Clinton campaign had not shied away from pledging to increase taxes on the very rich, but John Smith’s office was cautious about adopting too much of Clinton’s policy platform. David Ward told IFTC, “the US is a very different country, it doesn’t have an NHS, for example,” he said, “you’ve got to be very careful trying to translate policies across.”

“For me the real lesson was organizational; the discipline, and how well-oiled the Clinton campaign was, particularly in an age that is now long gone: pre-internet, when people were using fax machines.”

There were excellent reasons to look to the the US Democrats for effective campaign strategies. Following Labour’s policy realignment under Neil Kinnock and the Policy Review in 1989, the ideological division between Labour and the Conservatives was more blurred. The UK now looked more like the US two-party system, where the ideological differences between Republicans and Democrats were much slimmer. The Democrats were more accustomed to running campaigns in this environment. US campaigns are also bigger and more expensive, offering a glimpse at new technologies and approaches.

The Clinton campaign was also highly effective at reaching their target voters: the middle class. When Clinton took office, nearly three of four middle-class voters said he understood the problems of people like them. He repeated clear simplistic messages relentlessly and centralised messaging so that it came from a single source, all strategies that Labour would adopt in the run up to the 1997 election.

Clinton’s war room operation and rapid rebuttal strategy had been a valuable asset on the campaign trail and a possible blind spot for Labour in its own 1992 general election. The party had not responded to direct attacks on Kinnock , preferring to keep the conversation focused on policy and avoid the quagmire of personality politics, whereas Clinton confronted attacks quickly and head on, even if that meant giving them oxygen in the national media, and even when the accusation was highly personal in nature—like marital infidelity.

Byron E. Shafer, professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s department of political science, spent two decades in the UK studying elections and voting before returning to the US. He believes that Labour was too slow to recognise the arrival of the US-style personality politics.

“People were giving me wrong answers about how things work in the US and how they work here and they were not accurate on either. They had this notion that it doesn’t matter [who the candidate is], it just matters that it is a conventional labourite and they have clear themes—because in Britain, personalities don’t matter.”

Philip Gould and Patricia Hewitt appear to have shared this view. Among the recommendations published in their 1993 essay, Learning from Success—Labour and Clinton’s New Democrats, was the need to redirect attention from policy to the process by which it was delivered and the projection of competence.

Blair wants to adopt more than just campaign strategy

In January 1993, Blair and Brown organised a visit to Washington, stirring instant consternation in the party. David Ward recalls John Prescott contacted John Smith to ask why the pair were going.

Peter Mandelson, Director of Communications for the Labour Party at the time, recalled that Smith considered the visit to be “boat rocking”. “I always remember John Smith called me up and said ‘Why are there people going to America? Why are they going to do all this Clinton stuff ‒ this sort of modernisation stuff? We don’t need any more boat rocking’,” he said.

Blair returned from the visit convinced that Labour needed to overhaul more than just its campaign techniques, his perception was that Labour needed to veer towards the political centre to win. He was reportedly incandescent with rage that Labour was not taking on some of the same issues adopted by the Tories.

Within days of their return, Blair, Brown, and others invited Clinton pollster Stanley Greenberg and speechwriter Paula Begala, as well as aides Frank Greer and Elaine Kamark to London. “They were trying to push the idea that Labour had to follow the Clinton model very closely, and hence the Clintonisation story,” said David Ward.

This immediately provoked a backlash from those in the party apprehensive about trying to emulate the Democrats too closely. Clare Short accused them of running roughshod over Labour values by “chasing a Clinton myth.”

"There are people in our party who are obsessed with image rather than ideological conviction… Such people helped us to lose the last two elections, and they are about to draw exactly the wrong conclusions from Clinton's victory"—John Prescott

A February 1993 speech fuels further anxiety

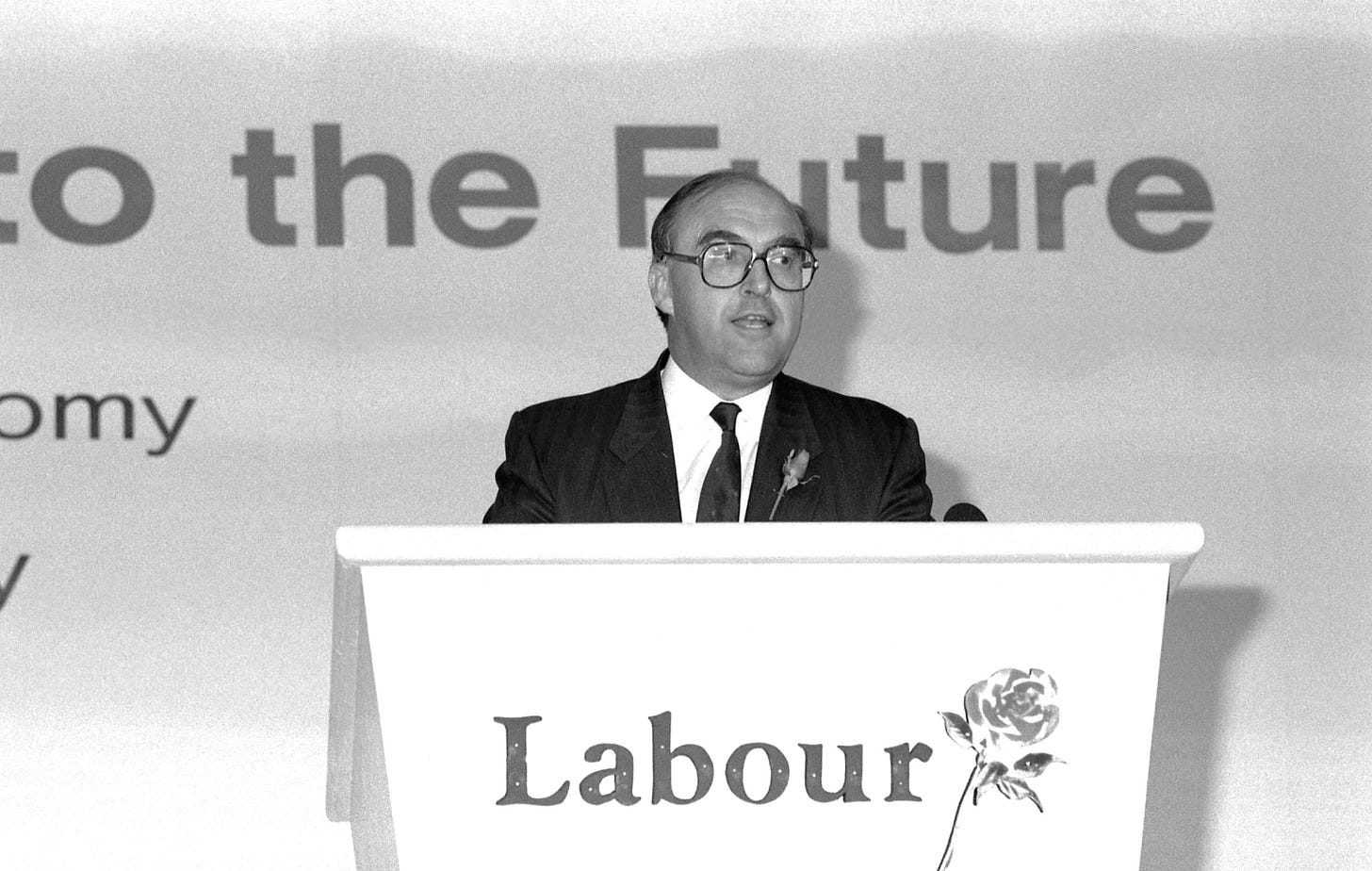

In the midst of the internal debate over what aspects of Clintonism would survive a trans-Atlantic voyage, Labour Leader John Smith delivered a speech on February 7 at the Labour Local Government Conference in Bournemouth that further provoked many on the left of the party.

Light on policy, Smith’s language was peppered with Clintonisms. He spoke of the need to create a “framework of investment” and “an infrastructure of opportunity” by “nurturing change as an ally.” The words “new” and “renew” appeared 25 times in 37 minutes, a similar frequency to Clinton’s Inaugural Address.

Smith insisted that nobody was transplanting US politics in the UK, but it didn’t reassure everyone. Dennis Skinner accused Smith of using Clintonism as “a stick to beat the trade union dog with,” and a cynical attempt to forsake Labour’s roots in socialism and abandon its traditional support base.

David Ward, who was involved in writing the speech is adamant that any resemblance to Clinton was coincidental. “I don’t remember sitting down thinking, ‘let’s write this using some specific Clinton language.’,” he said. “Smith’s agenda about investment in the extraordinary skills of ordinary people and a bias towards an investment-led economy, all of that is very familiar Labour stuff from the 1989 Policy Reviews.”

“It is not a surprise that Clinton and the Democrats had a core message about investing in people and advancement of opportunity. He was targeting particular voting groups. We would have all done the same.”

John Smith died before he could put the campaign lessons learnt from the Clinton campaign to use under his leadership. Labour performed well, however, in the local elections and European elections in 1994, suggesting the campaign lessons were well understood. “I’m sure that New Labour and Blair applied all those lessons in Millbank,” said David Ward. “But we would have done the same.”